Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl was one of the best books I have read for the Read The World challenge, and so I thought I would read this as well. It is, again, a compilation of verbatim transcripts; presumably somewhat edited, if only to remove the interviewer’s questions and comments, but with the rhythms and untidiness of normal speech. This time, it is people associated with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan: soldiers, nurses, bereaved mothers and widows (although no Afghan voices). The title comes from the zinc coffins that were used to deliver bodies back home.

The English edition was published in 1992, and the introduction stresses the comparison with the US experience in Vietnam; soldiers returning home from an unpopular war and being told it was all a mistake, and the impact on the country’s self-image. There are of course also many differences. The USSR kept an iron grip on the news coverage, at least initially; this book’s publication in 1990 is symptomatic of the loosening up of the glasnost/perestroika era. It’s depressing to think how Putin’s government might respond to a similar book about Ukraine or Chechnya.

The other obvious parallel, of course, is with our own recent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. There is never a shortage of wars to write about, after all. In the end, that made this a less remarkable book, for me, than the Chernobyl one; it is not quite as unique and weird. But it is still fascinating and insightful, and I recommend it. I would just suggest trying to read it in small doses; I found when I read too much in one go, the individuality of the voices started to blur a bit.

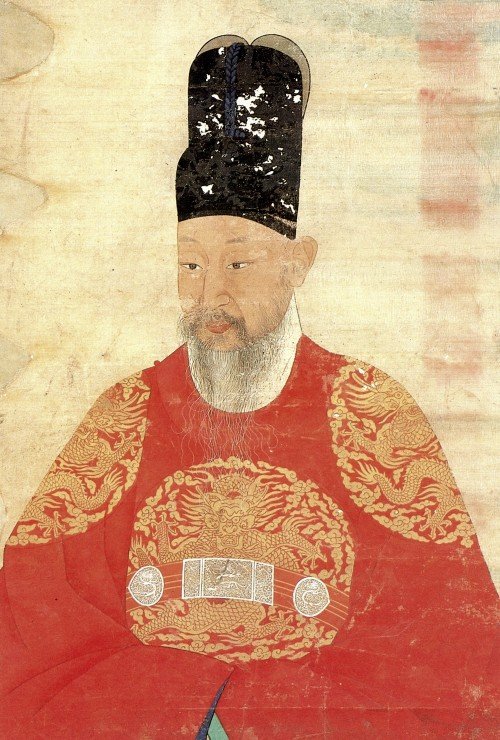

» The photo of a Soviet helicopter-tank operation is from the Department of Defense publication Soviet Military Power, 1984, via Wikipedia. It’s a public domain image because it was created by the US government.