Full title: Stamping Grounds: Exploring Liechtenstein and Its World Cup Dream. It’s Connelly’s account of following the Liechtenstein national soccer team during their qualification matches for the 2002 World Cup. After my previous book from Liechtenstein for the Read The World challenge turned out not to be from Liechtenstein at all, this one is at least about the country, even if it’s written by an Englishman.

You can see why he thought it would be a good subject for a humorous football book; there is something fascinating about these tiny countries, fielding largely amateur teams that lose nearly every game they play and almost never score a goal. On the one hand, if you were an amateur playing your club football in the third tier of the Swiss league (Liechtenstein isn’t big enough to have its own league), it would be a terrific opportunity to play against some of the finest players in Europe in front of tens of thousands of people. But how do you cope, psychologically, with playing for a team that almost literally never wins a game?

The answer, perhaps not surprisingly, is that they adjust their expectations about what ‘success’ means. If they make their opponents work really hard to score, that’s a success; scoring themselves is a triumph. They didn’t in fact score in that campaign; their greatest moment in the book is losing only 0-2 to Spain at home. Which is admittedly impressive for a country with only 30,000 inhabitants, 10,000 of whom are foreigners who aren’t eligible for the national team.

In the end, though, the book was underwhelming. Liechtenstein just isn’t very interesting: it’s a tiny, mountainous country with an enviable standard of living, thanks to its healthy financial sector (i.e. it’s a tax haven); basically a microscopic Switzerland, without that country’s famous flamboyance. Connelly spends much of the book trying to work out what it means to be Liechtenstein, what distinct national character there is to separate it from Switzerland or Austria; it turns out there isn’t anything.

I think Connelly does a reasonable job with weak material; he gets chummy with some of the players, and interviews all the key members of the Liechtenstein FA, and tries to dig up a few local characters, but it feels a bit like squeezing blood from a stone.

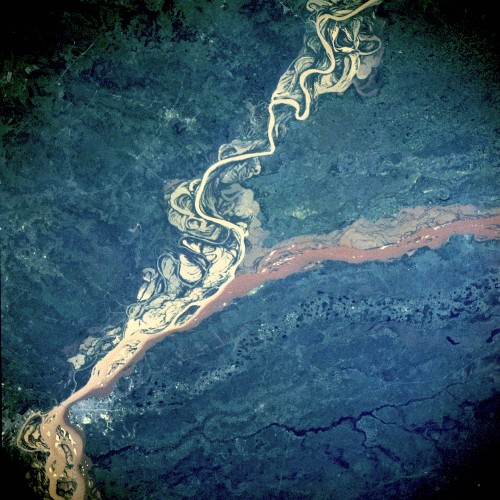

» The photo is of a Scottish fan in Liechtenstein for their Euro 2012 qualifier. Tartan Cephalopod is © Robin Skibo-Birney and used under a CC by-nc-nd licence.