I highly recommend this fascinating book; it seems to be out of print, but there are lots of second-hand copies on Amazon. As the title suggests, it’s about poor mad George III. And even Americans, brought up to think of George III as a tyrant, might have a little sympathy for him after reading this.

It starts with a detailed account of his illness—or his illnesses, really, since he initially suffered from relatively brief bouts, separated by long periods of good health. Having offered a diagnosis of porphyria, which is a hereditary condition, Macalpine and Hunter examine the medical histories of George II’s relatives and demonstrate that porphyria can be identified, with varying degrees of confidence, in a startling number of them; most notably perhaps in James I, Mary Queen of Scots and Frederick the Great of Prussia.

The book then moves on to a survey of C18th psychiatry, both in terms of its theoretical basis and treatment, and looks at the way it developed. Not surprisingly, George’s illness had a huge impact on the mad-business because of the publicity surrounding it. The idea of a king being forcibly confined in a strait-waistcoat focussed people’s minds on the treatment of the insane. The book traces developments in the treatment of patients and the law surrounding insanity, both in terms of treatment and things like criminal responsibility. Finally it looks at the way developments in psychiatry have affected historians’ portrayal of George III.

It is, as I say, fascinating. The account of his illness is remarkable, not least because of the political chaos around it. It was just the moment when, although Britain was increasingly recognisable as a modern democracy and decision-making increasingly rested with the Prime Minister and parliament, the king was still an important enough figure that his incapacity led to a crisis. And since the question of whether or not to establish a Regency depended on it, and a Regency would mean a change of government, his treatment was incredibly politicised. His doctors issued regular bulletins about his status, which were pored over by all concerned; his doctors themselves became associated with different political factions and found it very difficult to agree on anything.

Meanwhile the king was kept from his loved ones, frequently confined to a strait-waistcoat, and was subjected to a variety of unpleasant and intrusive treatments—bleeding, cupping, blistering, emetics—none of which, we now know, did him any good at all. And at least one aspect of his treatment, a ‘lowering’ diet without any meat in it, will have been actively making him worse.

Still, interesting though all that is, it was starting to get a bit repetitive—thoroughness is a great quality in a historian, but doesn’t always make for riveting reading—and I was glad to get past the details of George’s case and onto the broader stuff, which I found fascinating. For example, as psychiatry increasingly worked under the theory that mental illnesses are self-contained and separate from physical illnesses, the king was retrospectively diagnosed with ‘manic-depressive psychosis’ , and all of his various and violent physical symptoms—pain, fast pulse, colic, sweating, hoarseness, stupor—were interpreted as hysterical, or even as invented by the Court to disguise the truth of his condition.

And because it was assumed that he must always have been manic-depressive, the diagnosis colours historians’ portrayals of his whole personality:

Watson, in the standard Oxford history of the reign, writes : ‘He lacked the pliability and easy virtue of less highly strung people. When his obstinacy encountered an immovable obstacle, all his resources were at an end and the black humour claimed him… Madness was but this mood in an extreme form.’

The book quotes a whole series of similar descriptions. But the king’s early biographers presented a completely different picture, and in fact, we now know that between bouts of illness, sufferers from porphyria can be very healthy. Macalpine and Hunter are pretty scathing about psychiatry generally; the book was written in 1969, and it would be interesting to know whether they thought there had been any progress in the meantime.

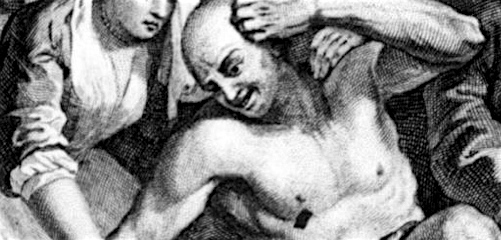

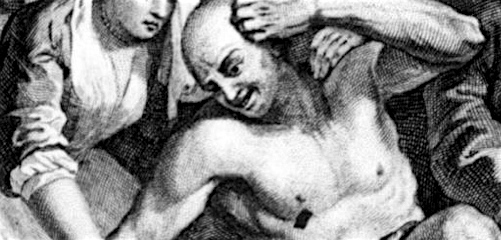

» the pictures are details from ‘The Interior of Bedlam’, the final scene in Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress. It predates the king’s first bout of madness, so the fact that one of the inmates thinks he is the king is not a jibe at George III. I got the picture from this site about the history of Missouri’s first state mental hospital.