-

'Our forebears considered casting a “secret ballot” cowardly, underhanded, and despicable; as one South Carolinian put it, voting secretly would “destroy that noble generous openness that is characteristick of an Englishman.”'

Tag: history

The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters

The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters, edited by Charlotte Mosley, is a selection of letters between the various Mitford sisters, who were an extraordinary bunch. From oldest to youngest: Nancy was the novelist who wrote Love In A Cold Climate and The Pursuit of Love; Pamela was least remarkable; Diana married Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists; Unity went off to Germany and became a personal friend of Hitler; Jessica ran away from home to join a cousin fighting on the communist side in the Spanish Civil War, and became a civil rights activist and writer in America; and Deborah, the only surviving sister, is now Duchess of Devonshire and spent most of her life working to make Chatsworth House into a profitable outfit.

Among the notable names that crop up: Hitler, Goebbels, Churchill, Harold Macmillan, General de Gaulle, JFK, John Betjemen, Evelyn Waugh, The Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the Queen, the Queen Mother, Prince Charles, Princess Diana, Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Noel Coward… so there’s lots of good material there.

The main interest in the early part of the book is the Big History stuff: the Nazis and Hitler most of all. I read it trying to get some sense of what appealed to Unity and Diana about Fascism, but although there are lots of letters about Hitler, and going to rallies and so on, I never quite got a handle on it. I suspect that for Diana, it was as much because of her attraction to Oswald Mosley as any ideology, but it can’t have just been that. And Unity seems to have had an with Hitler before she met him in the way someone might have an obsession with Elvis or Princess Diana. She found out where he regularly went to eat and kept going there until she had the chance to wangle an introduction.

I suppose since half of Europe went Fascist in the thirties, there’s no need for a special explanation. The same thing appealed to them as to everyone else: whatever that was. It’s perhaps easier to look back and empathise with the appeal of communism, but still, with that too it would be interesting to know what triggered it: was there some particular conversation or book? What would be enough to make Jessica run off to Spain in pursuit of it?

As the book goes on and the sisters get older and less active, the focus narrows down from these Big Issues onto their family dynamics, which are often made rather tense by the growing interest in them and the various books and TV programmes made by themselves and others. It’s still fascinating, though.

It helps that they all write well: their letters are chatty, funny, sometimes serious, and frequently quite bitchy. Nancy had the sharpest edge, but they all had their caustic moments. I probably ought to quote something, so here’s a fairly random bit that I thought showed a sharp eye. This is Diana writing to Deborah in 1960; Max is her son. He’s the Max Mosley currently in the news, as it happens.

Yesterday Max fetched me in the Austin Healey Sprite & drove me to Oxford where Jean had made a delicious middle day dinner. The flat is marvellous, not one ugly thing, & a view over playing fields to real country & a garden with an apple tree. ALL the wedding presents were being used — your car, Desmond’s china, Emma’s Derby ware, Viv’s pressure cooker, Muv’s pink blanket on the bed and (pièce de résistance) Wife’s coffee set — also of course Freddy Bailey’s canteen of silver.

Oh Debo, the pathos of the young. Don’t let’s think.

Charlotte Mosley, who edited the book, is daughter-in-law of Diana, so one wonders if she is, or could be, completely objective — it’s impossible to know whether she has quietly laundered anything out, and apparently, even at 800 pages, what appears in the book is a tiny percentage of the total — but I thoroughly enjoyed it.

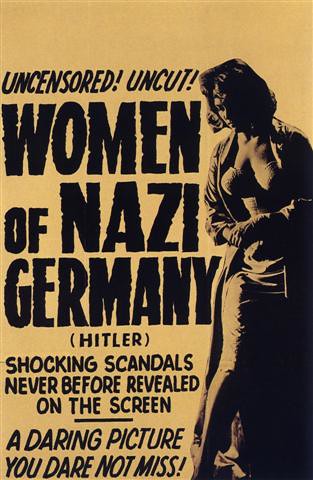

» the image, which has nothing to do with the Mitfords beyond the obvious, is POSTER – WOMEN OF NAZI GERMANY, posted to Flickr by Bristle’s Film Posters [ W1 ]. If it’s working, that is: Flickr seems a little flaky today.

Links

-

Fascinating essay over at MTMG about a footballer called John Cameron and the early history of English football.

-

Interesting article about 'sign names' – i.e. the nicknames deaf people give each other to save spelling out names letter by letter. Via Big Contrarian.

Links

-

'to summarize his views on Christianity, Thomas Jefferson set to work with scissors, snipping out every miracle and inconsistency he could find in the four Gospels… and reassembled the excerpts into what he believed was a more coherent narrative'

Links

-

Interesting. 'It is widely believed that Charles Darwin avoided publishing his theory of evolution for many years… This essay demonstrates that Darwin's delay is… overwhelmingly contradicted by the historical evidence.' via Carl Zimmer

The Invention of Tradition

The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, is a selection of essays by different historians. To quote the blurb:

Many of the traditions which we think of as ancient in their origins were, in fact, invented comparatively recently. This book explores examples of this process of invention […]

There’s a great quote in the section on the British monarchy. This is Lord Robert Cecil in 1860, after watching Queen Victoria open parliament:

Some nations have a gift for ceremonial. […] This aptitude is generally confined to the people of a southern climate and of a non-Teutonic parentage. In England the case is exactly the reverse. We can afford to be more splendid than most nations; but some malignant spell broods over all our most solemn ceremonials, and inserts into them some feature which makes them all ridiculous… Something always breaks down, somebody contrives to escape doing his part, or some bye-motive is suffered to interfere and ruin it all.

150 years later, the British have bigger, more pompous and more gilt-ridden ceremonies than almost anyone, and we see ourselves as especially good at pageantry: the opening of parliament, coronations, jubilees, royal weddings and funerals, and all of it presented as though it was ancient continuous tradition. And in fact much of the content, at least for the coronation, is ancient: it’s just that between the early 17th and late 19th centuries, the preparation was generally half-arsed and the results shambolic. Apart from anything else, the symbolism was awkward; Britain was a democracy of a sort, and as long as the monarch was a partisan political figure people were reluctant to surround them with all the trappings of divinely-provided power. It was only once the monarch was reduced to a figurehead that we could safely put them in the centre of these grand pantomimes.

The book also has an essay about the Scots (all that twaddle about clan tartans) and the Welsh (druids and the Eisteddfod), but those stories were broadly familiar, so in some ways the bits I found most interesting were about the British inventing traditions out in the Empire. For example, in India, where they had the problem of how best to assert Imperial authority over a ‘country’ which was in fact hundreds of small kingdoms held together by force, and how to project Queen Victoria as the focus of that authority while she was thousands of miles away. And although the British had been in India for a long time by then, this represented a new focus, since it was only in the wake of the Sepoy Mutiny/India’s First War of Independence in 1857 that control of India was taken from the East India Company and taken over by the state.

So in 1876 they held the ‘Imperial Assemblage’ to mark Victoria’s accession to her imperial title as ‘Kaiser-i-Hind’ when Indian kings/princes/maharajas gathered with their entourages at a site near Delhi to take turns to approach a pavilion decorated in British heraldic imagery, and each was presented with a banner which had a coat of arms in the European heraldic tradition, designed for the occasion by a Bengal civil servant called Robert Taylor. It sounds like an extraordinary event: apart from the basic weirdness of it, the scale was immense; ‘at least eighty four thousand people’ attended in one role or another. Sadly I haven’t managed to find a picture of the event, but below is the banner presented to Rajabahadur Raghunath Savant Bhonsle, the ruler of Savantvadi.

Thinking about all this reminded me of my own little moment of inventing tradition. When I was at university, there a couple of people at my halls of residence who wanted to start an all-male discussion club where the members would take turns to present a little speech on some interesting topic, and then everyone would drink sherry and discuss. A couple of friends and I took great delight in coming up with a ludicrously silly constitution for the club, which laid down arcane traditions and provided bizarre titles for the various officers. For example, every meeting was supposed to start with ‘the toasting of the Pope’: a different Pope each week, working through them in chronological order from St Peter onwards. There was no Catholic connection, pro or anti; I think it was just that the phrase ‘the toasting of the Pope’ was amusing. In the event there was one meeting and then the club fizzled out. And a good thing too, frankly.

Actually, though, the whole episode was rather fitting; after all, the University of Bristol itself is an institution whose landmark building is a vast Gothic edifice built not in the middle ages, or even at the height of the Gothic Revival in the mid C19th, but in 1915. Pretending to be older than it is — pretending to be Oxbridge, really — is what Bristol does.

Anyway, the book is interesting; some of the essays are better than others — Hobsbawm’s own contribution struck me as especially weak — but I’m glad I read it. A slight typographical gripe: irritatingly, quoted passages are marked only by the left margin being indented exactly as much as the first line of each paragraph is indented, which makes it extremely unobvious which paragraphs are quoted. I’m not suggesting that’s a reason to avoid the book; I was just irritated by it.

» img364, posted to flickr by Black and white archive, shows the 1953 Coronation celebrations in Edith Road, Smethwick. The banner is from the British Library.