-

'Xavier F. Salomon, Curator at Dulwich Picture Gallery, describes how he discovered a missing fragment of Veronese’s Petrobelli Altarpiece, thought lost.'

-

British wrestling posters from c. 1960s – 1990s

-

via Super Colossal

-

Amusing video.

Tag: museums and galleries

Darwin and wildlife photography at the NHM

I went along to the Natural History Museum to visit a couple of exhibitions: Wildlife Photographer of the Year and Darwin.

The WPotY exhibition is an annual treat; some years are better than others, but it’s never less than enjoyable. My long-term gripe is that the overall winner is almost always a portrait of a large charismatic mammal (usually one of the African big games species) rather than ever being a picture of a shrimp or a toadstool or something. This year I’m willing to give them a partial credit on that front; they’ve picked a picture of a big cat, but it’s the fabulous, rare and extremely elusive snow leopard, and the picture, a night-time shot with falling snow, is pretty great.

You can see all the pictures online, but they also put the show on in other venues around the UK and around the world, so if South Kensington isn’t convenient you still might be able to see it somewhere near you. The shot above is of a polar bear at sunrise. Cool, innit. And how about this one, of leafcutter ants carrying petals:

The Darwin exhibition, part of the build-up to his 200th birthday next year, takes us through his life and work, and is full of artefacts (notebooks, letters) and specimens he collected. It does a good job of telling us about his life, I think, although as I’ve read two biographies of Darwin, and the Voyage of the Beagle, and The Origin of Species, and a biography of his grandfather, and one of Huxley, most of the material was familiar to me. I did enjoy it — it’s good to see all his scribbly handwriting and there are some great items on show — but none of it was really news to me, so I may not be the key audience.

btw, if you’re going to the museums at South Ken, you could do worse than have lunch at Casa Brindisa. Brindisa are a Spanish food importer with a shop in Borough Market who now have three tapas bars, and the lunch I had in there was just excellent. The website has the menu on it, so I can tell you exactly what I had: the pan fried sea bream with morcilla de Burgos and Bierzo peppers, a herb salad with moscatel vinaigrette and a serving of patatas bravas. It was all really delicious; the fish was crisp and perfectly cooked and went beautifully with earthiness of the morcilla and the slightly spicy peppers; the salad was fresh and herby with just enough slightly sweet dressing, and the potatoes were golden and crunchy without being oily and not drowned in the sauce. They even make an excellent cup of coffee, which is almost harder to find than a good plate of food.

‘Byzantium 330-1453’ at the Royal Academy

The latest blockbuster exhibition at the RA is Byzantium 330-1453. It’s a big show, but then it does survey a millennium’s worth of art from a big empire.

It’s odd; I think most people who have even a general interest in history and culture have some knowledge, however sketchy or inaccurate, of classical Greece, Rome, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance. But the thousand year-history of Byzantium is somehow not part of that, and I was very aware going around this exhibition of how little I knew. It makes you think that perhaps the Great Schism of 1054, which separated Catholic and Orthodox christianity and so in some sense split Europe into east and west, is the pivotal moment in the continent’s cultural history.

[ Editorial aside: every time I start to say anything I find myself very aware of my ignorance. But even at the best of times I tend to hedge opinions around with qualifications, and for stylistic reasons there’s a limit to the amount of verbiage I can hang onto a sentence. So let me say up front: I don’t want you to think that I think I know what I’m talking about. I don’t. ]

Voltaire apparently described Byzantium as ‘A worthless repertory of declamations and miracles, a disgrace to the human mind’, and there seems to have been a general dismissal of Byzantine culture by a lot of western writers. I’m not sure the exotic and peculiar version in Yeats’s poems is actually any more flattering, either. Perhaps it’s because if you’re from the tradition that sees the Middle Ages as a regrettable regression between the classical civilisations and the Renaissance, Byzantium looks like a bit of a mistake: they started as Romans, spent a few centuries developing a medieval aesthetic and then stuck with that for the next 500 years until the Renaissance came along and moved art forward again.

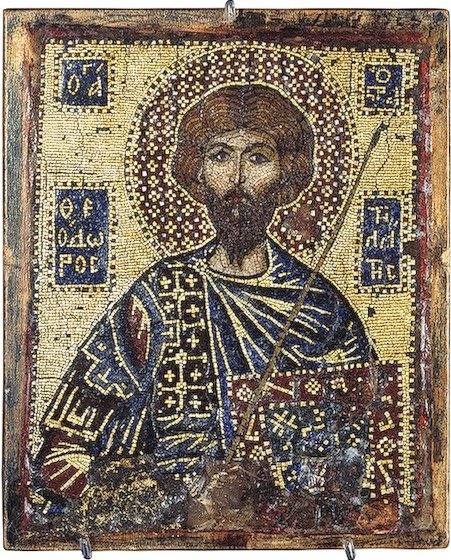

Or at least, I imagine the ‘stuck in a rut’ theory is a horrible caricature, but there does seem to have been a somewhat rigid artistic culture. The exhibition leaflet explains that between 730 and 843, the Byzantines had an iconoclasm. Which firstly means, of course, that a lot of the early transitional art was destroyed.* But also, to quote the exhibition leaflet, ‘Following the failure of iconoclasm the Triumph of Orthodoxy was celebrated in pictures and with an explosion of artistic activity. … Orthodoxy was declared to be the use of icons; and icons declared the nature of Orthodoxy.’

Whether it’s because of the strong identification of a artistic tradition with a religious identity, or because the icons were seen primarily as devotional objects rather than artworks, to my untrained eye they all look very similar. And indeed if you see, say, C19th Russian icons, they still all look fairly similar. It’s like statues of Lenin in the USSR: originality really wasn’t the point. In fact, when it came to statues of Lenin, originality would probably have been actively suspicious; I don’t know if the same dynamic is at play with Byzantine icons.

Anyway, getting back on to more solid ground: you should go to see this exhibition because it has lots of nice stuff in it. Icons, of course, both painted and in the slightly ridiculous medium of micromosaic; lots of carved ivory; manuscripts, featuring all sorts of attractive scripts, mainly Greek but some Arabic, some Cyrillic and some completely mysterious; chalices and other items inlaid with precious stones and fabulous little enamel designs; jewellery, coins, ceramics and textiles. The first few rooms are chronological, but other rooms are arranged by theme: ecclesiastical objects, domestic objects, icons, the interaction between Byzantium and the West, the influence of Byzantium on nearby cultures and so on. It is, as I said, a big exhibition, and a lot of the items are small, finely worked objects that really deserve close examination, which is never easy in a busy gallery; I don’t think there’s any straightforward solution to that, though.

The exhibition website isn’t very comprehensive, although there’s an education guide in PDF form which has some nice pictures.

* incidentally, there’s a lot of discussion around at the moment of science vs. religion, and whether science is compatible with religion; meanwhile defenders of religion point to the great works of devotional art from the Hagia Sophia and El Greco to Bach. It’s worth pointing out that art and religion haven’t always had the easiest relationship either, which is why so many English churches are the proud owners of statues that have head their heads knocked off.

» the picture is taken from the website of the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, although the work, a tiny 9 × 7.4 cm C14th icon of St Theodore Stratilates in mosaic, is in the RA exhibition.

Renaissance Faces at the National Gallery

Renaissance Faces: Van Eyck to Titian is an exhibition that does exactly what the title the suggests: it’s a selection of portraits by van Eyck, Titian, Raphael, Holbein, Botticelli, Dürer, Cranach and their contemporaries. Room after room of rather solemn looking people — no smiling for portraits back then — wearing their most expensive-looking velvets and furs and damasks. So if that’s the kind of thing you like, and on the whole I do, you’d probably like this show.

About half the pictures are from the National’s permanent collection, which sometimes seems a little bit like cheating; but there are some very good paintings they’ve borrowed from elsewhere, it’s interesting to see them all together, and it’s not actually a chore to have another look at van Eyck’s Arnolfini portrait, or the Bellini portrait of the Doge, or Holbein’s Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling.

For me the finest picture in the exhibition is the Titian portrait of Pope Paul III which normally lives in Naples. It really is one of those works which seems transcendent even by the standards of a great artist. The Pope sits there, engulfed in these huge robes, looking physically old but sharp-eyed and full of power. And they have it hanging next to the portrait of Pope Julius II by Raphael from their permanent collection, painted fifty years earlier and an important influence for Titian’s portrait. They are both marvellous paintings and they make a fascinating contrast, stylistically and psychologically.

» The Raphael is the one at the top.

Flemish paintings at the Queen’s Gallery

I went yesterday to see Bruegel to Rubens — Masters of Flemish Painting at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace. I wasn’t really sure what to expect; you have to love Bruegel, but I’ve always found Rubens easier to admire than to enjoy.

It turned out to be just the one Bruegel on show, with seven or eight paintings by Rubens and a variety of other artists: Teniers, van Dyck, Memling and so on. Or to be strictly accurate, only one painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder; there are a couple by Jan Brueghel the Elder as well. You can see all the paintings on the exhibition website I linked to above.

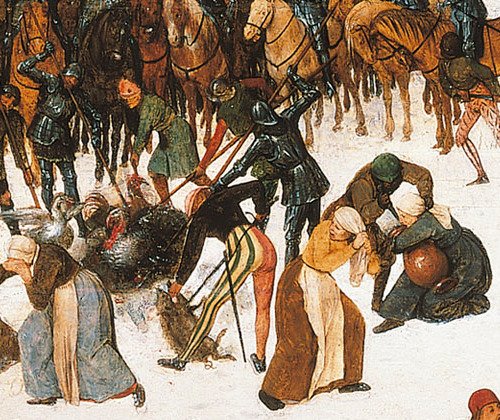

The Bruegel, Massacre of the Innocents, is a hell of a painting. The biblical story of the massacre ordered by Herod has been painted as set in a Flemish village, with the troops in Spanish costume, making it highly topical, apparently, because the Holy Roman Empire had been cracking down on the Netherlands in brutal fashion. The painting was then acquired by Emperor Rudolph II, who presumably for political reasons had the painting edited: all the massacred babies have been painted over to make the scene one of generic plunder.

So wherever you see a soldier slaughtering an animal, or a woman trying to hold on to a storage jar or a bundle of rags, you know that there was originally an infant. In some places, as in the detail above, you can almost make out what it originally looked like.

It really is one of those occasions when reality seems to be demanding to be used as a metaphor for something, but I shall resist.

The exhibition didn’t persuade me to love Rubens, or at least, not his mythological works or landscapes (though the painting Winter: The interior of a barn pleased me more than most). There were, though, two Rubens portraits which were really fabulous, particularly his self-portrait. Apparently an English nobleman bought a painting from Rubens, and Rubens, not knowing that it was actually intended for the king, fobbed him off with a mediocre work that was mainly painted by his workshop. The self-portrait was the piece he sent to the king as an apology.

It really is a gorgeous piece of work. It doesn’t make me like all those big pink women any more, but this painting at least is very very covetable.

» I got the pictures from this article about the exhibition. The Royal Collection’s website for the show is very good: all the paintings, I think, with commentary, so do check it out.

Francis Bacon at Tate Britain

I went to see the Bacon exhibition at Tate Britain today. And I enjoyed it, if enjoyed is the right word for work which is quite so bleak. He was an atheist who made a habit of painting crucifixions; and without the theology, a crucifixion is just a man being tortured to death.

So there were lots of trapped, screaming, contorted and frequently eviscerated figures, brutally unflattering portraits, and distinctly unhealthy-looking flesh. Which makes the work sound like some kind of chaotic stream of consciousness, but actually it seems tightly controlled: figures isolated in large plains of colour.

» Study of a Baboon, 1953, © The Estate of Francis Bacon/DACS 2008. Digital image © 2008, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. James Thrall Soby Bequest, 1979. Taken from the exhibition website, which is excellent as usual at the Tate.