I was searching around for a book from Malawi for the Read The World challenge, and found very cheap second-hand copies for sale of these two books of poetry by Jack Mapanje. And since poetry books are generally very short by nature, I thought I might as well buy both. Since I’ve read some fairly dreadful poetry as part of this challenge, it was especially encouraging that Skipping Without Ropes was published by a major poetry publisher, Bloodaxe Books. And I was drawn to The Chattering Wagtails of Mikuyu Prison because it had birds in the title. Yes, I really am that predictable. Also, if you want me to buy your wine, put a picture of a bird on the label.

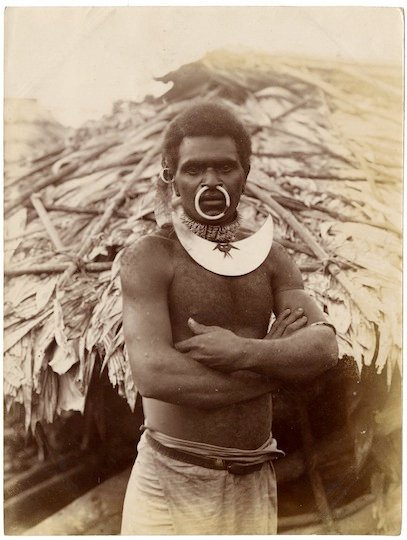

And on the subject of birds, the ones in question were almost certainly the species pictured above, African Pied Wagtail. Attractive little beastie, isn’t it. Apparently, they form large communal roosts, one of which was on the wire mesh over the courtyard of Mikuyu prison when Mapanje was locked up there for three years, without charge, for writing poetry which annoyed the regime. Quite a lot of his time in prison was apparently spent mopping up wagtail shit. He was released in 1991 after pressure from writers and human rights activists and moved to the UK; he currently teaches creative writing at Newcastle University.

And he writes well. His poetry is dense, allusive, with telling details and attention to the sounds and rhythms of the language. I wouldn’t say he was suddenly my new favourite writer but he is, as I hoped, a proper poet; in a completely different class to some of the writers I’ve read for the Read The World challenge. You can read, and hear him read, some of his poetry at the Poetry Archive; ‘Scrubbing the Furious Walls of Mikuyu’ seems like an obvious place to start.

I actually read the books in reverse order, because his later book, Skipping Without Ropes, arrived first. His later poems seemed to me to be more relaxed, both emotionally and stylistically. I think on the whole I preferred the earlier stuff: angrier, more tightly wound and densely written. The later poems are probably smoother and more polished, but sometimes wander a bit too close to prose for my tastes. But there’s plenty of good stuff in both.

» The photo, African Pied Wagtail (Motacilla aguimp), is © Arno Meintjes and used under a CC by-nc licence.