The Butterfly’s Burden is a translation of three books by the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish who died earlier this year: The Stranger’s Bed (1998), A State of Siege (2002) and Don’t Apologise for What You’ve Done (2003). It’s a parallel text edition, which always makes me feel terribly learned, but in practice is just a waste of trees since I can’t even read Arabic script.

I am writing this post without having read the whole thing, which may be an admission of defeat. I’ve been having some difficulty connecting to it. I’m not inclined to blame Darwish for that: I imagine it’s partially the basic awkwardness of reading poetry in translation which is, as they say, like eating a Mars bar with the wrapper on; partially a lack of contextual knowledge on my part; and perhaps partially down to the translation by Fady Joudah, although I’m not in a position to judge it as a translation. And of course, very likely because of my own biases as a reader.

I initially picked it up and dipped in at random, which wasn’t a success, so I sat down and read A State of Siege straight through from beginning to end, and actually I did quite get into it and enjoy it. So, heartened by that, I tried the same thing with The Stranger’s Bed, but despite a few moments where I thought I was getting somewhere, I found it a bit of a chore. There were images or passages or moments that I thought were striking or effective, but I felt that on some basic level I just wasn’t getting it; the whole wasn’t cohering into more than the sum of the parts, and I found it all a bit frustrating.

I will make an attempt on Don’t Apologise for What You’ve Done as well, but whether or not I finish it I’m still going to claim Darwish as my writer from Palestine for the Read The World challenge, because I read two of the three books, and I think that’s good enough.

For an extract I’m going to pick something from A State of Siege, since that was the book I enjoyed most; in a sense, though, it’s a more difficult piece to pick extracts from because it isn’t divided into separate poems. Instead, it’s a thirty-page poem built up of short lyrical fragments, separated on the page by a little typographical squiggle. They work together cumulatively, and the poem has a kind of reflective tone; they could be the journal entries of a slightly gnomic diarist, or the contents of a notebook. The poem was written during the Second Intifada, and the conflict is the central subject, but the poem circles around it, sometimes explicitly talking about politics and violence, sometimes about poetry or love.

❧

The mother said:

I did not see him walking in his blood

I did not see the purple flower on his foot

he was leaning against the wall

and in his hand

a cup of hot chamomile

he was thinking of his tomorrow …❧

The mother said: In the beginning of the matter I didn’t

comprehend the matter. they said: He just got married

a little while ago. So I let out my zaghareed, then danced and sang

until the last fraction of the night, when

the sleepless were gone and only baskets of purple flowers

remained around me. Then I asked: Where are the newlyweds?

Someone said: There, above the sky, two angels

are consummating their marriage … So I let out my zaghareed,

then danced and sang until I was struck

with a stroke.

When then, my beloved, will this honeymoon end?❧

This siege will extend until

the besieger feels, like the besieged,

that boredom

is a human trait❧

O you sleepless! have you not tired

from watching the light in our salt?

And from the incandescence of roses in our wounds

have you not tired, O sleepless?❧

We stand here. Sit here. Remain here. Immortal here.

And we have only one goal:

to be. Then we’ll disagree over everything:

over the design of the national flag

(you would do well my living people

if you choose the symbol of the simpleton donkey)

and we’ll disagree over the new anthem

(you would do well if you choose a song about the marriage of doves)

and we’ll disagree over women’s duties

(you would do well if you choose a woman to preside over security)

we’ll disagree over the percentage, the private and the public,

we’ll disagree over everything. And we’ll have one goal:

to be …

After that one finds room to choose other goals❧

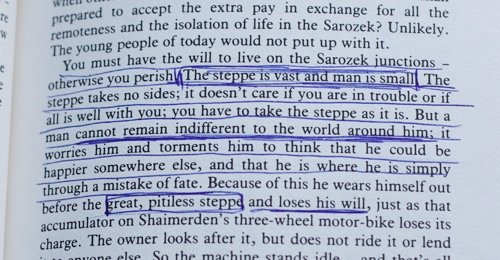

» The photograph is of Mahmoud Darwish’s funeral in Ramallah and is © activestills.org.