This novel tells the story of Yedigei, a worker at a remote railway junction in the middle of the Kazakh steppes. There’s a refrain which is repeated at intervals throughout the book:

Trains in these parts went from East to West, and from West to East . . .

On either side of the railway lines lay the great wide spaces of the desert — Sary-Ozeki, the Middle lands of the yellow steppes.

In these parts any distance was measured in relation to the railway, as if from the Greenwich meridian . . .

And the trains went from East to West, and from West to East . . .

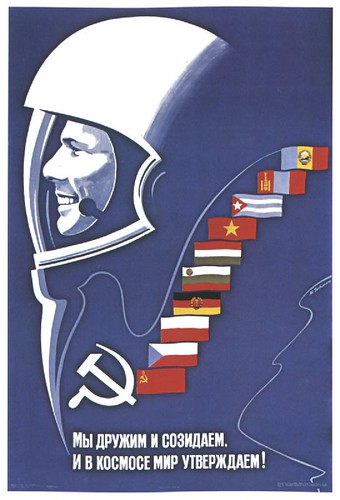

Yedigei is taking the body of a friend to be buried at a traditional cemetery out in the steppes, and his life story is told in flashback. The railway junction is near a rocket launch site, and running in parallel to Yedigei’s story is a strange subplot about cosmonauts making contact with an extraterrestrial civilisation.

Aitmatov was from Kyrgyzstan, and The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years is my book from Kyrgyzstan for the Read The World challenge. In some ways, though, it’s very much a book of the Soviet Union. It was written in Russian and is set in Kazakhstan, and one of the themes in the book is the tension between the traditional Kazakh culture and the Soviet bureaucracy.

Which isn’t to say it’s some kind of radically dissident novel; according to the introduction, Aitmatov (who died earlier this year) was a firmly establishment figure, a correspondent for Pravda, winner of a Lenin Prize and a State Prize for literature, and a winner of the Hero of Socialist Labour medal. The material which is most critical of the government is about things which happened under Stalin; presumably by 1980, when this novel was published, that was fair game.

Incidentally, this English edition was published in 1983 and it’s really strange to be reading all this stuff in the present tense. ‘He is a member of the Supreme Soviet, was a delegate to the last four Party Congresses…’ I wouldn’t say it makes me nostalgic exactly, but it is a bit of a throwback to my childhood.

In 1952 the summer was even hotter than usual. The ground dried out and became so hot that the Sarozek lizards did not know what to do; they lost their fear of people and were to be found sitting on the doorstep, their throats quivering, with mouths wide open, trying somehow to find shelter from the sun. Meanwhile, the kites were trying to get cool by soaring to such heights that you could no longer see them with the naked eye. Just now and again they gave themselves away with a single cry and then once more they became silent in the hot, quivering, mirage-laden air.

I really enjoyed this book. The setting is striking and atmospheric; the steppes of central Asia, punishingly hot in summer and snow-covered in winter, inhabited by foxes and eagles and camels, with just this one railway line running through it. And the fairly conventional human drama which anchors the book is intertwined with the science fiction subplot on one hand and bits of Kazakh folk myth on the other.

Here Yedigei is dealing with his magnificent but difficult camel, Burannyi Karanar:

That snowfall heralded the start of winter in the Sarozek, early and chill from the very first. With the start of the cold weather Burannyi Karanar became restless, angry and irritable, as once again his male instincts rebelled within him. No one and no thing could be permitted to encroach on his freedom. During this time even his master had to retreat on occasions and bow to the inevitable.

On the third day after the snowfall there was a frosty wind blowing over the Sarozek, and suddenly there arose a thick, chilly haze just like steam over the steppe. You could hear footsteps crunching in the snow far away, and any sound, even the faintest rustling, was carried through the air with exceptional clarity. The trains could be heard coming along the lines when they were many kilometres away. And when at dawn Yedigei heard the waking roar of Burannyi Karanar in the fold and heard him trampling and noisily shaking the fence behind the house, he knew only too well that he was in for trouble. He dressed quickly and stepping out into the darkness, walked over to the fold. There he shouted, his voice hoarse from the astringent air, ‘What’s this all about? Is it the end of the world again? You want to drink my blood? You lecherous beast!’

But he was wasting his breath. The camel, excited by his awakening passions, took not the slightest notice of his master. He was going to have his was, come what may. He roared, snorted and ground his teeth threateningly and broke down part of the fence.

Really it’s exactly the kind of book I hoped to find during this exercise: one I’d never heard of and would probably never have read otherwise, which introduces me to a part of the world and a culture I knew little about, but which is above all a really world-class novel. I’d recommend you buy a copy without extensive scribbles in biro all over it, though.

And one last thing, since I think it’s important to give credit to translators: translated by John French.

» the photo of a camel in front of Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan is © alexpgp and used under a CC by-nc-sa licence. Steppe eagle, Kazakhstan, posted to Flickr by and © rtw2007.