Part of the point of the Read the World challenge was to read things that would never have found normally. The Chronicles of Dathra certainly fits that description; it is self-published Kuwaiti chick-lit. According to the blurb:

Dathra is the story of a kind hearted pretty girl from Kuwait whose qualities are hidden beneath her excessive layers of fat and shabby fashion sense. Dathra, like everyone else, is trying to live her life to the fullest and find love. Only her insatiable appetite and irresistible cravings are getting in her way and subjecting her to the scrutiny of a society where looks are everything.

It feels like it’s aiming to be Bridget Jones’s Diary; but Bridget Jones is a basically healthy woman who wants to be a bit thinner but doesn’t have the commitment to diet properly, whereas Dathra is dangerously overweight and has an unhealthy psychological relationship with food. She lies to leave work early because she has a food craving; she eats enormous amounts when she’s upset; she has aggressive public tantrums when she can’t get the food she wants; she breaks up an engagement because of a disagreement over food; she puts herself into hospital by overeating.

So there’s some tonal weirdness going on, as the book comes across as darker and stranger than I think it means to. The book seems to have the same lack of self-awareness that it makes fun of in Dathra; neither of them are quite coming across in the way they intend. Or perhaps I’ve misjudged the author’s intentions completely.

It made an interesting change, anyway. Presumably there is an enormous variety of fiction being published all around the world all the time: thrillers, romances, sci-fi, chick-lit, and for that matter all kinds of literary fiction. But the tiny sliver of it that ever makes it into English translation — and few countries even have one book translated per decade — tends to all be much the same: serious, important, highbrow, and almost always political. Which is frustrating. This at least is a book written in the last few years about everyday life for wealthy but otherwise ordinary Kuwaitis.

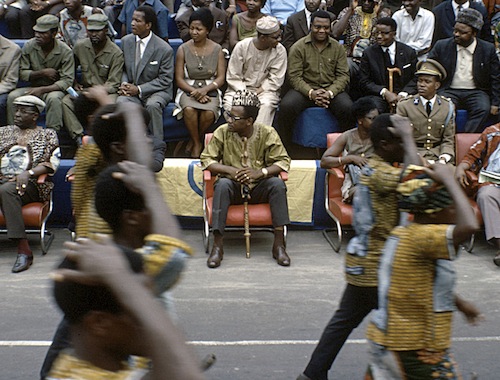

» The photo, ‘McDonald’s Drive Thru – Surra, Kuwait’, is © Samira/Mink and used under a CC by-nc-sa licence.