-

»Alphabetized Bible«, 2006, by Tauba Auerbach.

Year: 2008

Links

-

Autochromes are a kind of early colour photography. This one is particularly fabulous, but check out the whole set.

-

OK, fair's fair, this is quite funny.

-

via Make, things made by prisoners, including weapons, rope ladders, tattooing needles and so on.

-

'These poems are taken from Riffing on Strings (Scriblerus, 2008) and are reproduced with kind permission of the publishers.' I'm very keen on the *idea* of poems about science. Often ambivalent about the actual poems, though.

Links

-

Joss Whedon's online project. Which is actually very good and funny and stuff.

The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting is an exhibition of ‘the responses of British artists to the cultures and landscapes of the Near and Middle East between 1780 and 1930’. So the East here is Cairo, Jerusalem and Constantinople, and not Bombay, Singapore or Nagasaki.

You can hardly touch on the subject without a name-check for one of the few bits of cultural theorising that’s so famous that even I’ve heard of it, and the Tate mentions it right up front:

In the 1970s the Palestinian-American academic Edward Said published his treatise on Orientalism, initiating a global debate over Western representations of the Middle East. For many, such representations now appeared to be a sequence of fictions serving the West’s desire for superiority and control over the East.

So I went round with that argument somewhat in mind, and I had a yeah-but-no-but reaction to it. The Tate’s one-sentence summary of the argument — a sequence of fictions serving the West’s desire for superiority and control — makes it sound like a coordinated propaganda effort to push a particular agenda, and it clearly isn’t that; but then I imagine that Said’s original book was rather more nuanced anyway.

Yes, there’s a focus on the picturesque and the exotic, and a certain superficiality in the images, and some particular subjects which bring out the worst in the artists, like the slave markets and the harem. And I’m sure they did travel around with a bone-deep sense of their own culture’s superiority. But to offer a couple of points in lukewarm defence: firstly, this is tourist art. Most of the artists travelled in the region for a year or two, so it’s a rather more immersive kind of travel than most modern tourism, but still, these are visitors painting for the British market. I think much of the picturesqueness can be explained simply by their tourist status, without the need to invoke some kind of deep cultural agenda. Not that the two ideas are mutually exclusive.

The other point is this. The bulk of the work here is C19th, and when you look at C19th paintings on other subjects — scenes from Shakespeare, or the Bible, or British history, or even contemporary life — you see a similar tendency towards the picturesque, the colourful, the sentimental and the didactic. These were not people keen on ambivalence and self-doubt.

The one subject where cultural differences collide most spectacularly is the harem. Obviously, none of the male artists had ever been inside a harem — there’s not much point in sequestering your women if you let a load of nosy foreigners come in and paint them — and the idea of them came to occupy a rather sweaty part of the artists’ imaginations. The harem paintings in this exhibition are relatively tame (apparently French versions had rather more flesh on display), but they are clearly an opportunity to paint some exotic totty, rather than a sensitive and nuanced exploration of cultural difference. There’s one painting by a woman who had actually been inside a harem, and apparently it caused a minor sensation at the time for revealing what the harem was really like: not in fact a rich, tapestry-draped, incense filled hothouse full of scantily clad odalisques, but a rather plain domestic interior full of woman doing boring domestic stuff.

Other paintings were perhaps not exotic enough. There’s a great scene in Brideshead Revisited, where Charles Ryder, having established his reputation as a painter of country houses and English scenery, has been on a trip to South America, and has been getting rave reviews for an exhibition of South American scenes when Anthony Blanche turns up, takes him to a seedy gay bar and precedes to eviscerate the pictures.

“Oh, the pictures,” they said; “they’re most peculiar.” “Not at all what he normally does.” “Very forceful.” “Quite barbaric.” “I call them downright unhealthy,” said Mrs Stuyvesant Oglander.

‘My dear, I could hardly keep still in my chair. I wanted to dash out of the house and leap in a taxi and say, “Take me to Charles’s unhealthy pictures.” […] and what did I find? I found, my dear, a very naughty and very successful practical joke. It reminded me of dear Sebastian when he liked so much to dress up in false whiskers. It was charm again, my dear, simple, creamy English charm, playing tigers.’

There was certainly something of that about the exhibition: a failure, for example, to communicate any sense of heat.

I chose the two paintings here because I like them, rather than because they’re typical. In fact, I like them because they’re not typical. Most of the paintings left me underwhelmed, and that’s my real problem with the show; it’s fairly interesting, but it didn’t excite me very often as art.

» The paintings, both taken from the exhibition website, are Sir Robert Shirley, Envoy from Shah ‘Abbas of Persia to the Courts of Europe, painted by an unknown artist before 1628, from the collection of R.J. Berkeley; and Arthur Melville’s An Arab Interior, 1881, from the National Gallery of Scotland.

Links

-

'This is clearly an illustration from some alternate Anne of Green Gables, one in which Marilla sends her away to an institution instead of keeping her, and grief renders her into a transcendental halfwit.'

The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters

The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters, edited by Charlotte Mosley, is a selection of letters between the various Mitford sisters, who were an extraordinary bunch. From oldest to youngest: Nancy was the novelist who wrote Love In A Cold Climate and The Pursuit of Love; Pamela was least remarkable; Diana married Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists; Unity went off to Germany and became a personal friend of Hitler; Jessica ran away from home to join a cousin fighting on the communist side in the Spanish Civil War, and became a civil rights activist and writer in America; and Deborah, the only surviving sister, is now Duchess of Devonshire and spent most of her life working to make Chatsworth House into a profitable outfit.

Among the notable names that crop up: Hitler, Goebbels, Churchill, Harold Macmillan, General de Gaulle, JFK, John Betjemen, Evelyn Waugh, The Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the Queen, the Queen Mother, Prince Charles, Princess Diana, Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Noel Coward… so there’s lots of good material there.

The main interest in the early part of the book is the Big History stuff: the Nazis and Hitler most of all. I read it trying to get some sense of what appealed to Unity and Diana about Fascism, but although there are lots of letters about Hitler, and going to rallies and so on, I never quite got a handle on it. I suspect that for Diana, it was as much because of her attraction to Oswald Mosley as any ideology, but it can’t have just been that. And Unity seems to have had an with Hitler before she met him in the way someone might have an obsession with Elvis or Princess Diana. She found out where he regularly went to eat and kept going there until she had the chance to wangle an introduction.

I suppose since half of Europe went Fascist in the thirties, there’s no need for a special explanation. The same thing appealed to them as to everyone else: whatever that was. It’s perhaps easier to look back and empathise with the appeal of communism, but still, with that too it would be interesting to know what triggered it: was there some particular conversation or book? What would be enough to make Jessica run off to Spain in pursuit of it?

As the book goes on and the sisters get older and less active, the focus narrows down from these Big Issues onto their family dynamics, which are often made rather tense by the growing interest in them and the various books and TV programmes made by themselves and others. It’s still fascinating, though.

It helps that they all write well: their letters are chatty, funny, sometimes serious, and frequently quite bitchy. Nancy had the sharpest edge, but they all had their caustic moments. I probably ought to quote something, so here’s a fairly random bit that I thought showed a sharp eye. This is Diana writing to Deborah in 1960; Max is her son. He’s the Max Mosley currently in the news, as it happens.

Yesterday Max fetched me in the Austin Healey Sprite & drove me to Oxford where Jean had made a delicious middle day dinner. The flat is marvellous, not one ugly thing, & a view over playing fields to real country & a garden with an apple tree. ALL the wedding presents were being used — your car, Desmond’s china, Emma’s Derby ware, Viv’s pressure cooker, Muv’s pink blanket on the bed and (pièce de résistance) Wife’s coffee set — also of course Freddy Bailey’s canteen of silver.

Oh Debo, the pathos of the young. Don’t let’s think.

Charlotte Mosley, who edited the book, is daughter-in-law of Diana, so one wonders if she is, or could be, completely objective — it’s impossible to know whether she has quietly laundered anything out, and apparently, even at 800 pages, what appears in the book is a tiny percentage of the total — but I thoroughly enjoyed it.

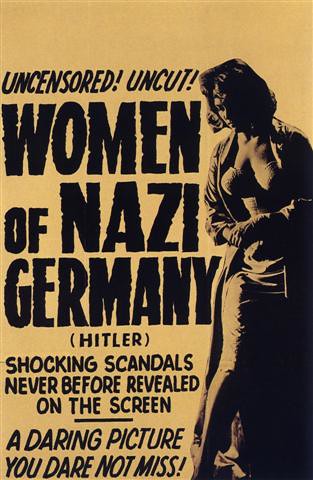

» the image, which has nothing to do with the Mitfords beyond the obvious, is POSTER – WOMEN OF NAZI GERMANY, posted to Flickr by Bristle’s Film Posters [ W1 ]. If it’s working, that is: Flickr seems a little flaky today.