Or, in Solomons Pijin, Bikfala Faet : olketa Solomon Aelanda rimembarem Wol Wo Tu. The first interesting thing about this book is the language. The entire text — i.e. the introduction and so on, not just the narratives themselves — is in Solomons Pijin first and then English translation. Which gives you a chance to compare the two languages. Pijin is of course a language derived from the use of English as a lingua franca in the region, so it is almost entirely based on English in vocabulary; but the grammar is quite different.

Here’s a bit of the Pijin; at first glance it looks completely impenetrable, but if you sound it out, you start to get a sense of how the pronunciation relates to English. It’s interesting to try to make sense of it, but I’ll put the translation in a footnote* so you can compare it.

Long 1939 wo hemi kam. Japan hemi bomem Pearl Harbour. Ating hemi 1941. An long time ia evri waetman stat fo toktok abaot wo. Toktok hemi stat fo go raon nao. So mi lusim Makira long taem ia an mi go long SDA mison long Bituna. Mi go primari skul tisa moa ia. Dea nao mi stap gogo wo hemi kam long Solomon Islands. Hemi kam long Rabaul an New Britain. So evriwan stat fo ranawe nao. Mi go baek long Munda an joenem Donald Kennedy, wea hemi Distrik Ofisa. Mi save long hem taem mi stap long Tulagi.

My knowledge of the Pacific theatre during WWII is very limited — the British tend to have a Europe-centred view of the war — so I didn’t actually realise when I ordered this book that the Solomon Islands were the site of some very serious fighting. In fact, although I didn’t know any details, even I had heard of Guadalcanal.

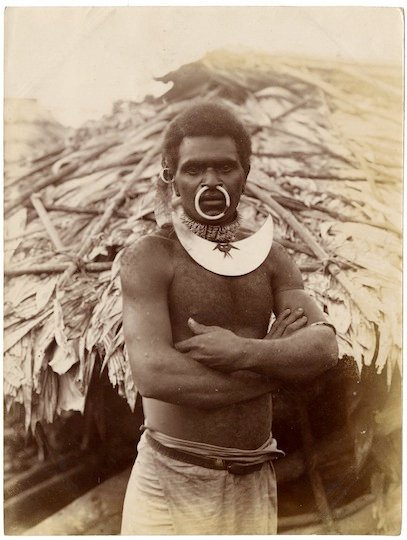

It’s really an extraordinary coming-together of cultures; the Solomon Islands was a genuine global backwater — they had apparently still been using stone tools when the British arrived at the end of the C19th, and some of their wartime heroics recounted in this book involve dug-out canoes — and then the full weight of the industrialised military power of Japan and America come and fight their way across the islands in a campaign involving tens of thousands of deaths, dozens of ships sunk and hundreds of aircraft destroyed.

Inevitably we tend to learn about these battles from the perspective of the major powers — and especially our own side. So it’s interesting to read accounts from people who just happened to be living in the path of the war. The people whose stories are in this book took a variety of roles: coastwatching; scouting with a slice of guerilla combat; fighting with the regular army; working in the Labour Corps. It’s interesting stuff with some real hairy action to it: paddling for miles around the islands under cover of darkness to return wounded US pilots to their base, going behind Japanese lines to mine a radar station. And the last story talks about the influence of the war on the political history of the Solomon Islands, and particularly the dissatisfaction created by the contrast between how well they were treated by the Americans and how badly they had been treated by the British under colonial rule.

Sigh. Not that I feel much personal responsibility for the way that my compatriots behaved in the Solomon Islands decades before I was born, but it is a bit shameful. They took their land, paid them a pathetically small amount of money for their labour, and beat them. Then during the war the Islanders were very impressed to see that the black American soldiers wore the same uniforms and the ate the same food as white soldiers, and that the Americans soldiers would share food with the natives, and invite them into their tents and let them sit on the bed and talk to them in a friendly way; pathetically small things, really, but it goes to show what they had been led to expect by the British. And then when the Americans gave them various supplies, the British confiscated them, piled them up and burnt them, because… well, because they were dicks, seems to be the main reason.

Still, if you’re from a former colonial power and you read post-colonial literature, you have to expect to be the bad guys most of the time.

The Big Death is my book from the Solomon Islands for the Read The World challenge.

* In 1939 the war came. Japan bombed Pearl Harbour. I think it was in 1941. At that time all the whitemen started to talk about war. Rumours started to go around. So I left Makira at that time and went to the SDA Mission at Batuna. I went and became a primary school teacher there. It was there that I stayed until the war came to the Solomon Islands by way of Rabaul and New Britain. So everyone started to flee. I went back to Munda and joined Donald Kennedy, a District Officer I had known in Tulagi.

» The photograph of a Solomon Islander from the British Museum was taken by John Watt Beattie in 1906. Munda Deep Corsair – Solomon Islands is © whl.travel and used under a CC by-nc-sa licence. Seabees, 1945, was posted to Flickr by and is © TPB, Esq.