I think this is quite a fun idea — One Day In History.

Make history with us on 17 October by taking part in the biggest blog in history.

‘One Day in History’ is a one off opportunity for you to join in a mass blog for the national record. We want as many people as possible to record a ‘blog’ diary which will be stored by the British Library as a historical record of our national life.

Write your diary here reflecting on how history itself impacted on your day – whether it just commuting through an historic environment, discussing family history or watching repeats on TV.

Anyone who reads Pepys online will know that the interest lies as much in the minutiae – what he ate, the plays he went to, and just recently (or at least at this time of year 343 years ago), his doctor’s attempts to cure his constipation. So the material collected today genuinely might be of interest to future historians. There was a somewhat similar thing done over a longer period in the UK during the 40s and 50s called the Mass Observation Project, where people were encouraged to keep diaries, and the results have been made into a couple of books that I know my father enjoyed.

I’m afraid that any historians of the future wanting to know what people had for breakfast in the carefree days before the Great Squid Wars will have to manage without my input, though. But if any HotF is reading this: I had marmite on toast. ‘Marmite’ is a brand name for yeast extract sold as food. ‘Toast’ is what we call a slice of bread which has been grilled or ‘toasted’ in a special-purpose machine called a ‘toaster’. ‘Bread’ is a foodstuff made by powdering the seeds of a species of grass, mixing the powder with yeast and water, and…

In all seriousness, there would have to have been a truly mammoth cataclysm for some future historian not to know what bread is. Perhaps if the squid win the war and we all end up living underwater. Who knows what other things might seem interesting, though. It’s tempting to pick on stuff which seems shiny and new and typical of our age, like the internet, but actually it would take almost as profound a cataclysm to destroy the internet as to eradicate bread. Of course even if there’s still a network of connected computers, I daresay the user experience will be radically different. One of these days someone is going to get a working 3D display, for a start. Internet Explorer 36 will no doubt still be lagging behind the competing browsers in terms of implementing the latest technology. Sorry, that’s a very lame joke. In fact, it would be amazing if Microsoft was still a dominant company in 30 years, let alone a few centuries. By that time, Microsoft and Bill Gates will only survive as a faint memory as synonymous with money, like Standard Oil and Rockefeller and Carnegie.

The idea that the stuff of everyday life is sometimes more interesting than the Big Historical Events makes a neat connection with the exhibition I went to see at the V&A today, called At Home In Renaissance Italy. I vaguely had it in my mind before I went that it was going to be about everyday life for ordinary people. It wasn’t, of course; it was about everyday life for the mega-rich. ‘Home’ sounds so cosy, but in this case it refers to huge palazzos (palazzi?) full of all the most fabulous and luxurious stuff that money could buy. For example: the exhibition was divided up according to the different rooms of the Renaissance house, and the scrittoio (study) was illustrated using stuff from the study of Lorenzo de’ Medici. Apparently Lorenzo distanced himself from the family business, but his grandfather really was the Gates or Rockefeller of his day. Although Gates, bless him, doesn’t strike me as much of an aesthete, so I doubt if his own mansion is full of the kind of beautiful objects on display here.

The reason they focussed on Lorenzo for that part of the exhibition is that the V&A owns the ceramic panels from the ceiling of his study, although they’d borrowed stuff from other collections to complement it, including a lavish copy of Pliny’s Natural History which must be the most elaborately decorated secular text I’ve ever seen. Not surprisingly, a large proportion of the stuff in the show comes from the V&A collection, but the act of curating it into a well-organised exhibition easily justifies an entrance fee to see stuff that would be on show in the permanant display anyway. And there are lots of things which they’ve borrowed from elsewhere as well.

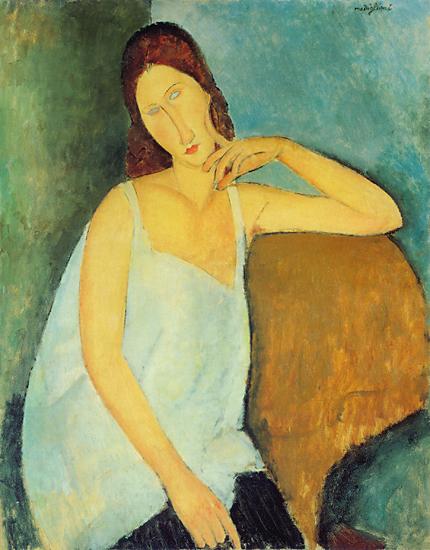

I felt that the exhibition made a bit of a statement when you walked in and were confronted by a pair of grand Veronese portraits, displayed together for the first time since they were moved from the room where they originally hung, and in front of them is a case with a sword like the one carried by the husband and a gold marten head like that carried by the wife (above). Which seemed a bit like saying ‘we’re so grand we can use a Veronese just to illustrate a sword’. And on the other side of the room was a Botticelli which served to illustrate the layout of a Renaissance house. This is presumably the curatorial equivalent of name-dropping. As well as some other fine paintings, including a couple of Lippis and a Crivelli, there was loads of interesting stuff — fireplaces, furniture, ceramics, glassware, board games, instruments, clothes, inkwells, spectacle frames, wafering irons — and I thoroughly enjoyed it.