Philip Zimbardo is the psychologist who ran the famous Stanford Prison Experiment [SPE] in 1971. The ultra-shorthand explanation is this: he took twelve normal young men and split them randomly into ‘guards’ and ‘prisoners’ then set up a fake prison. It was supposed to run for two weeks, but within six days the situation was so out of hand and the guards were mistreating the prisoners so badly that the experiment had to be abandoned.

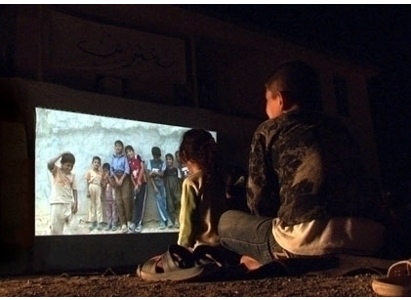

More recently he acted as an expert witness for the defence at the court martial of Staff Sergeant Chip Frederick, the man in charge of the night shift in the section of Abu Ghraib where the notorious photos were taken.

The full title of the book is The Lucifer Effect: How good people turn evil, and it’s an exploration of the processes by which normal people end up behaving in horrific ways. It starts with a detailed, almost hour-by-hour account of the Stanford experiment and an analysis of what we can learn from it, broadens out to talk about parallel situations, then gives a detailed analysis of the events at Abu Ghraib which explores where responsibility for the events there should best be placed.

I can see why the SPE has become iconic: it was a striking experiment and the account of it makes an interesting narrative. Still, I would be reluctant to extrapolate too much from just that. One key to a good experiment is surely that you control as many variables as possible so that you can accurately isolate cause and effect. The SPE by contrast set up a very complex situation in a very open-ended way. Reading this book, it comes across as him just throwing the situation together and waiting to see what happened. There are so many different factors that might be affecting the outcome, including simple chance.

I suppose if you want to investigate complex situations developing over time, you can’t have the kind of control that’s possible in a simple half-hour experiment with one or two participants in a lab, and I do think the SPE is interesting; I just would be reluctant to assume it proved anything very specific or definite.

The other thing that struck me was that the situation was much more loaded to start with than I had appreciated. I’d only heard the vaguest account of the experiment before I read the book and I guess I assumed that it was set up in a very generic way, and that the guards and prisoners developed their behaviour quite spontaneously just on the basis of the jobs they had been given. That’s not entirely true. Zimbardo actually set up the experiment because he wanted to study the psychological effects of imprisonment. The idea was to put normal people in a prison environment and see how the situation affected them, so he was keen to create a suitably tough regime. He told the guards that was what he wanted. The guards had mirrored sunglasses and billy clubs (which they weren’t allowed to use on the prisoners), the prisoners were wearing shapeless smocks and had to respond to their numbers all the time instead of their names.

Again, I can see the reason for all that—to create a convincing prison—but since the interest in the experiment is now normally taken to be the behaviour of the guards, not the prisoners, it’s worth pointing out that they were primed to behave badly. It wasn’t quite as spontaneous as I’d thought.

Just how badly they treated the prisoners is still remarkable, even so. Endless verbal abuse and humiliation, roll-calls all the time, even in the middle of the night, done over and over again forwards and backwards, pointless, repetitive tasks, solitary confinement in a cupboard for hours at a time. A striking sign of how bad it got was that one of the prisoners went on hunger strike: this is someone who was in a psychology experiment and could have left at any time, but got so fixed into the prisoner mindset that they started starving themselves in protest at conditions. Zimbardo himself, playing the role of the warden, got so involved in the dynamic that he started worrying about managing the prisoners as though it was a real prison.

Of course, if the message is simply that good people will, in the right circumstances, do evil—well, we shouldn’t need a psychology experiment to teach us that. The classic rhetorical focus for that argument is the Holocaust; given the sheer number of people involved, they can’t all have been born evil. Even the Holocaust, if it was an unparalleled event, might be a one-off; some kind of freak combination of circumstances. But there are thousands of possible examples. Many of those working on the Atlantic slave ships were no doubt models of honesty, generosity and trustworthiness with their families and friends. And there’s Rwanda, Nanking, My Lai, lynchings, the Cultural Revolution, all those East Germans who informed on each other to the Stasi, as well as countless examples of brutality by soldiers, police and prison officers.

In fact, it takes very little thought to see that it must be true that a large proportion of evil acts are committed by normal people. Perhaps the most striking thing is that we find it so difficult to make the imaginative leap: to believe that it could be you or me doing those things, that the ‘normal person’ could be any of us.

Still, one thing that makes the SPE notable is that the guards had so little motivation for their behaviour. I know I said they were primed to be aggressive, but they had no other motivation comparable to the examples above. They weren’t in a war zone, they didn’t stand to gain money or career advancement, and the prisoners weren’t part of some kind of stigmatised group—terrorist, criminals, Jews, Tutsis or whatever. Of course they didn’t actually massacre them either, and analogies between this kind of mistreatment and genocide need to be drawn with care. But it’s interesting even so that they got so caught up in the situation; especially since, unlike the prisoners, they were able to go home between shifts.

Anyway, that’s enough going round in circles about what lessons you can or can’t draw from the Stanford experiment. The other major theme of the book is the mistreatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Zimbardo specifically doesn’t say that situational pressure absolves people from responsibility for their actions, and in the case of the Abu Ghraib scandal, the guards clearly behaved appallingly. But he does question the version of events put out by the military and the White House after the event, that it was just the actions of a few ‘bad apples’. He raises the possibility that it was a ‘bad barrel’ and that we must also ask who made the barrel. His analogy, not mine.

That argument seems watertight. The US Army’s own internal reports specifically attach blame to people higher up the chain of command, and the very best interpretation would be that the prison was appallingly badly and negligently run. The staff had very little training and very little clear guidance about what was or wasn’t acceptable, the prison was totally overcrowded, the chain of command was unclear, no-one was coming to check up on them, and they were under enormous stress because they were living under appalling conditions, were overworked and the prison was under regular mortar attack. The relationship between the Military Police (who ran the prison) and Military Intelligence (who did interrogations) was not properly defined. Even if you don’t accept a more sinister explanation, it seems clear the the running of the prison was incompetent and chaotic.

The bigger questions are whether it was just down to badly trained, badly managed staff under extreme stress, or whether it was part of a broader culture in the US military; and eventually whether it can be traced to policy decisions.

Prisoner abuse certainly wasn’t unique to Abu Ghraib. Hundreds of cases of abuse have been investigated in Guantanamo, Iraq and Afghanistan, and I don’t think you have to be overly cynical to feel that they may only represent a small proportion of the real cases. And apparently as of November 2004, that included at least five cases of prisoners dying during interrogation. Perhaps they had pre-existing heart conditions and those deaths were just bad luck; but given that one prisoner died in Abu Ghraib while left hanging naked from the wall by his arms (an ‘interrogation technique’ the Spanish Inquisition had a special term for, apparently), one suspects they were in fact tortured to death.

One thing that becomes clear is that the abuses at Abu Ghraib were relatively mild compared to some. Talking about a base near Fallujah

One of Fishback’s seargeants testified, “Everyone in camp knew if you wanted to work out your frustration you show up at the PUC tent [prisoners were called PUCs, “persons under control”]. In a way, it was a sport. One day [another sergeant] shows up and tells a PUC to grab a pole. He told him to bend over and broke the guy’s leg with a mini-Louisville slugger, a metal bat. As long as no PUCs came up dead, it happened. We kept it to broken arms and legs.”

The final question is whether all this abuse is the ‘normal’ behaviour of stressed and badly trained soldiers in a war zone—which would still be a pretty damning comment on the training and discipline of the US Army, given how widespread it appears to be—or whether it can be traced to specific policy decisions. Here the water is murkier. You’re in the world of the CIA, Military Intelligence and special forces, all people who are professionally secretive anyway. And even within that atmosphere of rarified machismo and hard-nosed realpolitik, people know that torture is a hard sell with the electorate.

Zimbardo has no doubt that there is sufficient evidence to trace the blame all the way up the chain of command. Starting with the people running Abu Ghraib and going up through the ranks, he puts a sequence of people ‘on trial’, culminating with George Bush. It’s actually a rhetorical device I’m uncomfortable with. Identifying responsibility is a valid exercise, but with such a sensitive and important subject as the problem of evil, I would prefer a writer who at least maintains a pretence of analytical distance. Zimbardo is a little too fond of theatrical turns of phrase. For that matter, it’s not a book I would recommend for its prose style generally:

The seeds of evil that blossomed in that dark dungeon of Abu Ghraib were planted by the Bush administration in its triangular framing of national security threats , citizen fear and vulnerability, and interrogation/torture to win the war on terror.

Still, despite my misgivings about how he frames it, I basically agree with the conclusion. For me, it’s sufficient to pick up just two things. The first is the decision to ‘legally’ exempt themselves from the Geneva convention by claiming that prisoners are ‘enemy combatants’ rather than POWs. The other is the notorious memo that redefined ‘torture’.

It held that physical pain must be “equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.” In line with this memo, in order to prosecute anyone charged with torture crimes, it is necessary that it must have been the “specific intent” of the defendant to cause “severe physical or mental pain or suffering.” “Mental torture” was narrowly defined to include only acts that would result in “significant psychological harm of significant duration, e.g., lasting for months or years.”

Which allows plenty of scope for inventive interrogators to do things which most of us would recognise as torture. Indeed it implicitly grants them permission to do so.

Those two things are enough for me. I don’t need a direct chain of orders that can be traced from the Pentagon to Tier 1-A at Abu Ghraib; it seems clear that Rumsfeld, Cheney and Bush believe that their employees should be able to torture people. Indeed, they probably pride themselves on taking the kind of tough decisions that wishy-washy liberals in the cloistered comfort of their book-lined studies would recoil from. Who knows; perhaps they only envisaged it happening in urgent interrogations of high-risk terrorist suspects, rather than every two-bit military prison in Iraq. Perhaps they just don’t give a damn.

I remember when they first started shipping people to Guantanamo I felt uneasy about it, but it was soon enough after 9-11 that it seemed like the situation might just be serious enough to justify skipping some of the formalities. If you had told me that people would be tortured there, and kept there for years, not just without a full-blown criminal trial but without a trial of any kind, I’m not sure I would have believed you. I don’t expect American governments to behave like that. America’s preferred image of itself as the freest, fairest country on earth and a beacon to oppressed people everywhere has always been a bit questionable; they’ve always been willing to prop up nasty regimes when it seems convenient, and even for American citizens I’m not sure the US is significantly freer and fairer than, say, Sweden. But there is some truth to it; I think it is important and a Good Thing that the richest, most powerful country on earth is a secular democracy with a free press, an independent judiciary and the rule of law.

Any moral authority derived from that has been cheerfully pissed away over the past few years. I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised, given some of the darker points in recent British history. Particularly, the fact that many of the ways of torturing people without just beating the crap out of them were developed and refined by the British security services in Northern Ireland, and for much the same reasons: a wish to break prisoners quickly and still be able to plausibly deny that what you’re doing is torturing them.

And it would be a pity if the main message anyone took away from this book was ‘Bush Cheney Rumsfeld: bad’. It wouldn’t matter how bad their intentions were if we could rely on the normal people at the bottom of the food chain to just say no: to refuse to abuse prisoners, to report abuse on the part of their comrades. But what I take away from this book is that evil is normal. It is to be expected that people will do appalling things if the circumstances are right. It is within all of us to be that person.

It’s a depressing conclusion and rather a depressing book, but I do recommend it; it is a thorough, interesting and thought-provoking. There’s also a website.