As part of my ongoing quest to read a book from every country, I picked up Shadows of your Black Memory as a book from Equatorial Guinea. It is a childhood/coming of age novel that sets up the conflict between traditional and western cultures: particularly in this case between traditional religion and Catholicism.

Which, at this point in the exercise, is not a description that fills me with excitement; because nearly all the literature of the post-colonial world seems to be about the conflict between tradition and western culture and/or modernity. Certainly the stuff which makes it into English translation. And it’s also pretty common to tell it as the story of a young person growing up caught between two worlds.

So I didn’t pick it up with much enthusiasm, but actually it’s a really good novel. It is simply very well written: vivid, fresh and engaging.

Here’s one of the Catholic bits:

When I was eight, I knew Father Claret’s catechism by heart, and my favourite book was his Straight and Sure Path to Heaven. The horror of eternal condemnation didn’t allow me to be a child. I didn’t go to the Wele River with Ba any more, I couldn’t learn how to make those bamboo toy cars that I loved so much even though cousin Asumu offered to teach me many times. I didn’t carve arrows to shoot at birds anymore, I didn’t go swimming in the Nganga River with my friend Otunga or my cousins Anton and Mbo. Even today I don’t know how to swim. I didn’t have a hunting dog, and I didn’t know how to make a cage for trapping fish. All this was for other children now, for the ones who weren’t fortunate enough to be touched by the grace of God. What’s the use of all that fun and idleness if in the end your soul is damned forever? Father Claret, the saintly one, asked me this as I read his book, and I had no choice; I had to acknowledge that the most important part of my life was my soul, and to be saved I had to avoid useless amusements, the silly games of my friends, my cousins, the brothers in my tribe. It was shortly before I was nine when I got into the habit of saying Mass from a little altar I made for myself in my room in front of the crucifix Father Ortiz had given me and under the religious things I had on the wall: the Eye-of-God triangle and some prints that were brought to me by my father’s white friends; the Little Prayer Book served as missal. Alone in my room, when no one was looking, when my little brothers succumbed to the midday sun, I got all dressed up in a bed sheet and pretended it was a priest’s chasuble and started to say Mass, in nomine Patris et Filii et Spritus Sancti, and I made the sign of the cross: I, a sinner, confess to Almighty God and the Blessed Mary Ever Virgin, Saint Michael the Archangel, John the Baptist, and to Apostles Peter and Paul and all the saints, and I beat my little breast in contrition, mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa, and I almost forgot the kyrie eleison kyrie eleison Christe eleison Christe eleison, then the intraito, oremus, and I turned my head ceremoniously; then in silent fervor I genuflected, gloria in excelsis Deo, and I recited it all without knowing what I said in a Latin I learned from listening to Father Ortiz so much.

So, yup, I really enjoyed this one. Well worth picking up. I’d be quite interested in reading the sequel if it was available in English. And I often forget to mention translators, but credit is certainly due in this case, so: the translation is by Michael Ugarte.

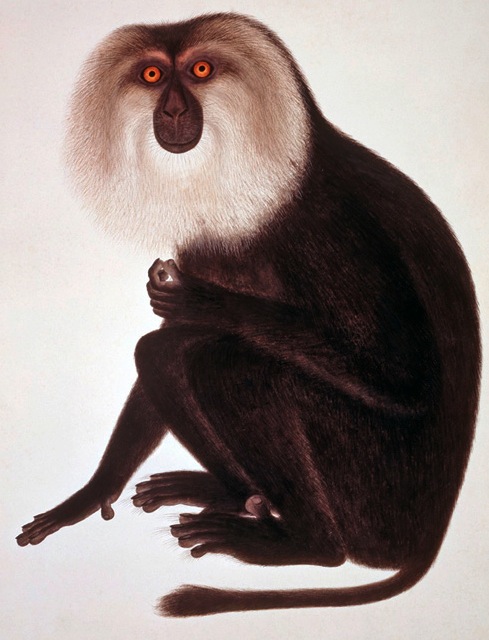

» The photo is of a Reliquary Guardian Figure (Eyema-o-Byeri) in the Brooklyn Museum. It is actually from Gabon rather than Equatorial Guinea, but it’s the right ethnic group (Fang).