So I went along to see the BM’s exhibition of medieval reliquaries. Which was a pretty amazing display of medieval craftsmanship: rock crystal, enamel, ivory, glass, and lots and lots of gold.

I didn’t enjoy it as much as I might have, though, because by the time I got there I had a bit of a headache. And it really didn’t help to be peering at lots of spotlit, shiny gold, trying to make out all the exquisitely worked detail. When I came out I had to take shelter in a dark quiet pub and nurse a pint of orange and soda for a bit.

I actually think gold is a slightly unrewarding material for this kind of thing. The overall effect is spectacular; particularly, presumably, in a dark church lit only by candles: bright, shiny, warm, glowing. But the very shininess makes it much harder to pick out the fine details of the craftsmanship; it was more rewarding, I think, looking at the fine work in materials like ivory and alabaster.

Apart from the sheer quality of the exhibits, it was anthropologically interesting. The scale is staggering, apart from anything else; there was apparently one church [I think somewhere in central Europe, from memory] which had 19,000 relics. It must have been a huge industry; not just the relics themselves, but the reliquaries, altars, altarpieces. And that was just the start of it. All that religious paraphernalia — the chalices and patens and thuribles — the ecclesiastical robes, the figures of saints, the murals, the stained glass windows; the whole business must have provided employment for thousands and thousands of workers. Goldsmiths, carpenters, stonemasons, painters, embroiderers, all employed primarily to produce religious objects, either for the church or for private devotion. The Reformation must have been economically catastrophic for them: it was effectively a whole economic sector disappearing.

The other striking thing, and I know it’s not exactly an original observation, is how ludicrous the relics often are. The foreskin and umbilical cords of Christ probably win the prize in that respect, although all the other relics directly associated with Christ also tend to strain credulity: fragments of his manger, bits of True Cross, thorns from the crown, the spear that pierced his side, the sweat band, the magic sponge, all of which were claimed as relics. If you don’t believe in miracles, it’s very difficult to get into the mindset of a society that sees them everywhere; but even so, surely people must have been dubious about this stuff? Perhaps the idea was that the genuineness of the prayer was more important than the genuineness of the relic, although they certainly didn’t act that way.

Going to this exhibition soon after going to the Horniman Museum exhibition Bali: dancing for the gods, I was left thinking how ritually impoverished my own life is as a (somewhat culturally protestant) atheist. Apart from the occasional weddings and funerals, just about the only festival I regularly celebrate is Christmas — and that only consists of gift-giving and turkey. I don’t even usually do anything about Guy Fawkes Night or Halloween, let alone Easter or saints’ days or whatever. I can’t say I feel I’m missing out on an important part of life, but maybe I am. It’s hard to tell how often these events were genuinely spiritual in nature, and how much they were a kind of entertainment in a society without novels, TV, cinema and computer games to keep them amused.

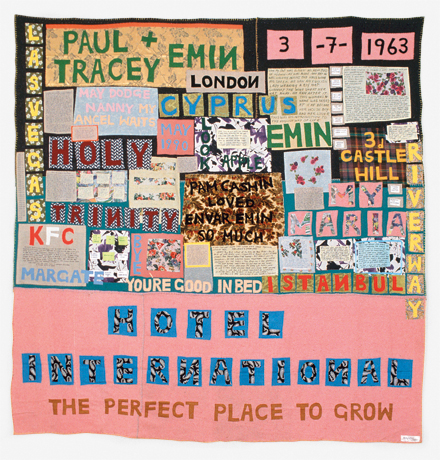

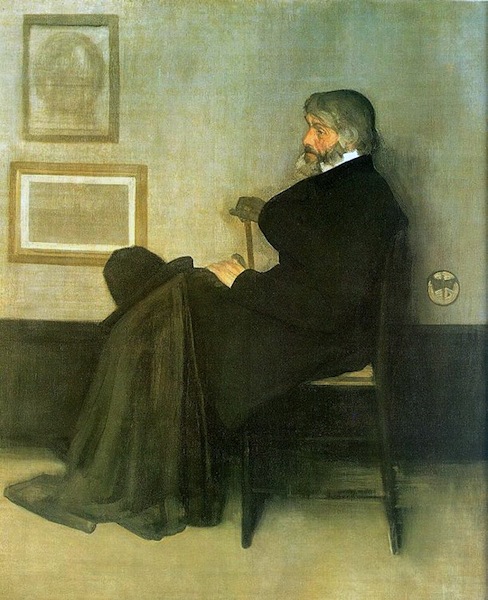

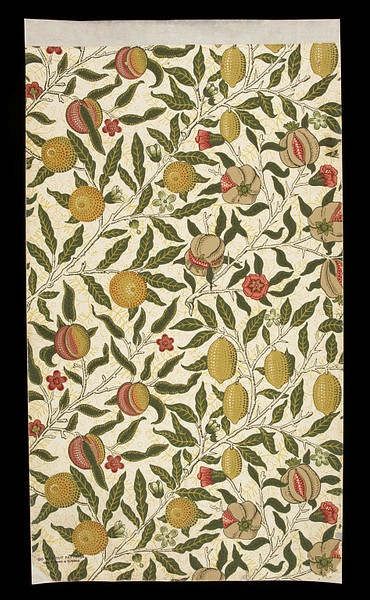

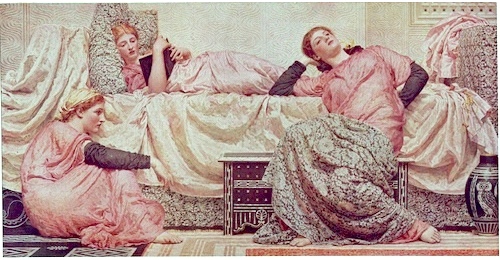

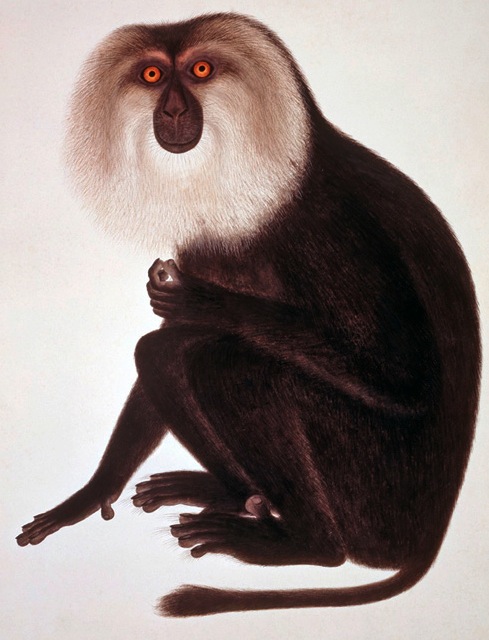

» The images are all from the British Museum collection, because those are conveniently online, although the exhibition has many items borrowed from other institutions.

Top is the St Eustace Head Reliquary, German, ca. 1210.

Then a reliquary cross in cloisonné enamel and gold, Constantinople, early C11th. The Virgin is flanked by busts of St Basil and St Gregory Thaumaturgus.

The little bundle is a relic of St Benedict, one of over 30 relics in a single German portable altar from 1190-1200.

Last is the iron bell of St. Cuileáin in a copper alloy shrine, from Ireland, a C7th-C8th bell in a C12th shrine.