I went to the last of three films I had booked at the London Film Festival yesterday (notes on which at the end of the post). The LFF, for those who don’t know, is the antithesis of a festival like Cannes: instead of being a big jamboree for people in the film business and the media, it is aimed squarely at the public. Basically, it’s a lot of films being shown at a selection of London cinemas.

And it is a LOT of films; 197 features and 112 shorts this year, apparently. All kinds of films: new British films, world cinema, restored classics, documentaries, gala screenings of big forthcoming releases to provide a bit of glamour. Which is great, but what usually happens is that I think ooh, the film festival, I should book some tickets and then I forget to do it.

But this year, I remembered. My instinct was to look for the stuff which was unlikely to get a wide release, so I went to some fairly obscure films, and I found it interesting how full the cinemas were. You might think that showing nearly 200 different films in a fortnight would spread the audience a bit thin. After all, there are cinemas in London that show less commercial films all year round, and I reckon that normally on a Friday afternoon, a Kyrgyz movie would play to largely empty seats; but they had sold out a medium-sized cinema. I guess it’s similar to the way that in a big city, you often find a place where a whole load of, say, shoe shops are clustered together; the value of being somewhere where people go for shoes outweighs the disadvantage of the extra competition.

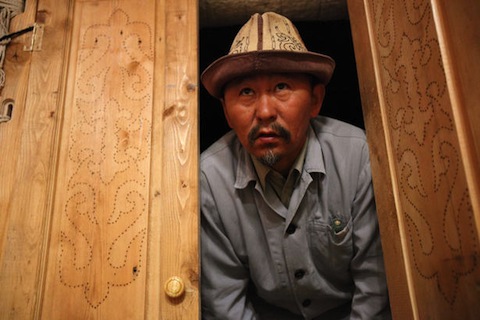

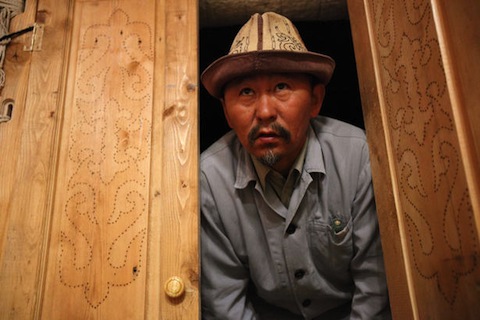

Anyway, the films; the first was The Light Thief. The ‘light thief’ is an electrician in a village in Kyrgyzstan who we start at the start if the film stealing electricity for villagers who can’t afford it. Without wanting to provide too many spoilers — what is the spoiler etiquette for a film I don’t actually think any of my readers are likely to see? — he gets caught up in village politics. And the film strongly implies that it is an allegory for the wider political situation in Kyrgyzstan, although that’s only an informed guess, given how little I know about the country.

The film looks beautiful; the dusty, windblown, mountainous central Asian landscape looks amazing in it. And there are some very nice embroidered felt hats and wall hangings and things. And it is funny and touching. So that’s a thumbs up.

Winter Vacation is a Chinese film about a group of youths killing time while waiting for their winter vacation to end in some battered, grimy, anonymous Chinese city. It’s well shot, and it has some genuinely funny dialogue, but it was a tiny bit soporific because it communicates the characters’ boredom and disaffection via the medium of long pauses:

Cut to shot of three people standing in the snow, looking at each other. Nobody speaks for a couple of seconds. Someone says something. Pause for another couple of seconds. Someone else replies. Pause again.

Which is quite effective, but it carries on like that for every scene in the whole movie, and it does wear a bit thin after a while. Slow is one thing, but actual stasis tests my patience. Still, there was a lot good about it, and it was listed in the ‘experimental/avant garde/artists’ films’ section, so I knew it might be hard work.

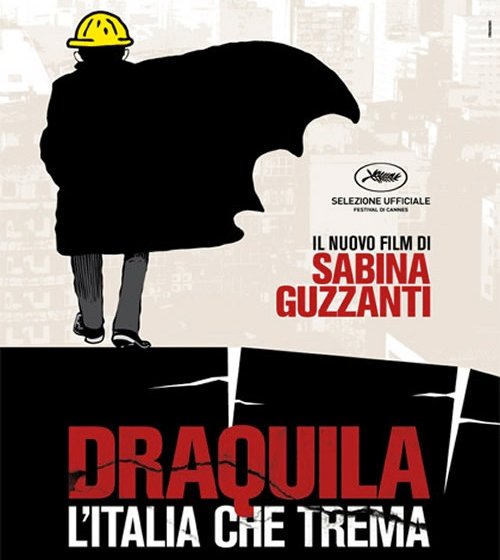

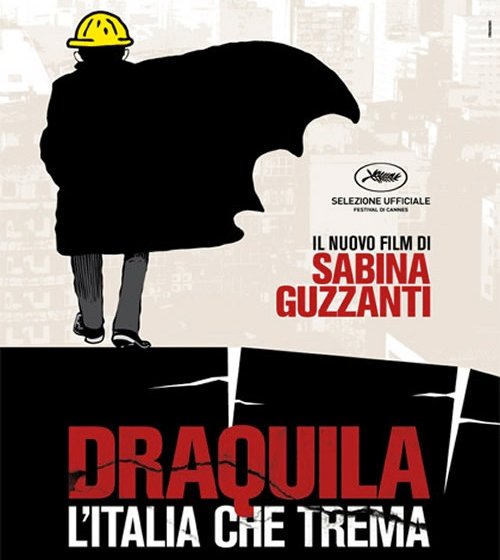

And finally I saw Draquila – Italy Trembles, which is a polemical documentary about Silvio Berlusconi’s handling of the aftermath of the earthquake in L’Aquila in 2009. I would strongly recommend you see this film if it comes to a cinema near you. It is funny and ferocious, and it paints a picture of a completely acquiescent, neutered Italian media, largely owned by Berlusconi, of an increasingly authoritarian government abusing the law to run roughshod over normal legal processes and rights, and massive, widespread corruption linked to the mafia. It’s not just a damning portrait of Berlusconi and Italy; what I found scary is that it provides a real sense of how a modern democratic country like Italy could slide towards fascism.

I should be clear about that: I’m not saying that Berlusconi’s government is fascist, or is likely to become so. But it does provide a sense of the slippage of normality. Already there is the confluence of government with crony capitalism and (I guess I should say: allegedly) organised crime; there is the eroding of civil liberties, the declaration of states of emergency as a way of bypassing the law, the increasing militarisation of the response to normal events. It is scary stuff.