Voices from Chernobyl was written in 1996, ten years after the reactor meltdown. It is an oral history of the disaster; that is, it’s presented as a series of ‘monologues’ by people who were involved in some way, with titles like ‘Monologue about War Movies’, ‘Monologue about the Shovel and the Atom’, ‘Monologue about Expensive Salami’. I’m actually a bit curious about exactly how they were collected; they are presented as verbatim transcripts, although I’m sure they’ve been tidied up somewhat. What you don’t get is any idea of what questions or prompting came from the interviewer. It’s quite an effective device, keeping the journalist out of the spotlight and letting the voices speak for themselves, but I assume there’s an element of artifice to it. I don’t think it detracted from the book, I’m just curious about the process.

The result is, anyway, an extraordinary book. The stories come from all kinds of perspectives: local farmers, soldiers, scientists, officials, construction workers, wives, children. And the material is fascinating: people’s accounts of being evacuated, of working on the reactor site, of nursing dying relatives. There are people who refused to leave, and people who came back because it was home, and people who, having fled conflicts elsewhere, moved to the area because there were houses lying empty. And overlying it all is the extraordinarily inept and chaotic government response, which included, for example, failing to distribute iodine or breathing masks because they thought doing so might cause panic.

And as well as the material being so interesting, it has a very literary quality; bleak and fatalistic, but laced with dark humour and absurdity, sometimes earthy, sometimes poetic. That poetry comes both from the real poignancy of the human situations and the surreal quality of many things that happened: the soldiers sent into the Zone to kill all the cats and dogs; the people whose job it was to dig up soil and bury it in pits; the fact that they were told that drinking vodka would help fight radiation poisoning, so everyone seems to have been rolling around in an alcoholic haze.

It really is a fabulous book. Here’s a little excerpt, from a man who has moved to live in the evacuated zone:

It’s easy to find books here. Now, an empty clay pitcher, or a spoon or fork, that you won’t find, but books are all over. The other day I found a volume of Pushkin. “And the thought of death is sweet to my soul.” I remember that. Yes: “The thought of death.” I am here alone. I think about death. I’ve come to like thinking. And silence helps you to prepare yourself. Man lives with death, but he doesn’t understand what it is. But I’m here alone. Yesterday I chased a wolf and a she-wolf out of the school, they were living there.

Question: Is the world as it’s depicted in words the real world? Words stand between the person and his soul.

And I’ll say this: birds, and trees, and ants, they’re closer to me now than they were. I think about them, too. Man is frightening. And strange. But I don’t want to kill anyone here. I fish here, I have a rod. Yes. But I don’t shoot animals. And I don’t set traps. You don’t feel like killing anyone here.

And here’s a bit by someone else, who moved back:

Sometimes I turn on the radio. They scare us and scare us with the radiation. But our lives have gotten better since the radiation came. I swear! Look around: they brought oranges, three kinds of salami, whatever you want. And to the village! My grandchildren have been all over the world. The littlest just came back from France, that’s where Napoleon attacked from once—”Grandma, I saw a pineapple!” My nephew, her brother, they took him to Berlin for the doctors. That’s where Hitler started from on his tanks. It’s a new world. Everything’s different. Is that the radiation’s fault, or what?

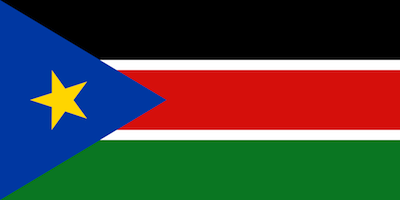

Voices from Chernobyl is my book from Belarus for the Read The World challenge. If you’re thinking ‘hang on, Belarus, that doesn’t sound right’, well, you’re right, the plant itself is in Ukraine, but it’s just by the border with Belarus and so Belarus was one of the worst affected places.

A quick namecheck for the translator, Keith Gessen, who I’m sure deserves a lot of credit for how well the book reads in English; and just to reiterate, I think this is a really good book and I strongly recommend it.

» There’s a whole load of photos around the web taken by tourists to the contaminated zone. Lots of pictures of the deserted town of Pripyat, particularly of peeling, empty schoolrooms. But after reading the book, they just seem too unpleasantly voyeuristic, so instead I grabbed a map of the contaminated area from Wikipedia.