Or to give it its full, bookshop-friendly title: This is Paradise! My North Korean Childhood, written by Hyok Kang with the French journalist Philippe Grangereau, and translated by Shaun Whiteside.

When I was looking for books from North Korea for the Read The World challenge, I was quite surprised I could only find two actually by North Koreans. The DPRK is such a bizarre Cold War relic that you might think there would be more interest in it. I guess reading about North Korea just doesn’t seem as important as reading about the Soviet Bloc did back in the old days.

Reading the reviews, it sounds like the other book, The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag, is probably the better of the two, but it seems to be focussed on life inside the labour camps. I decided to read This is Paradise! because it is about a more normal childhood in rural North Korea. Normal in North Korea being batshit insane by the standards of anywhere else.

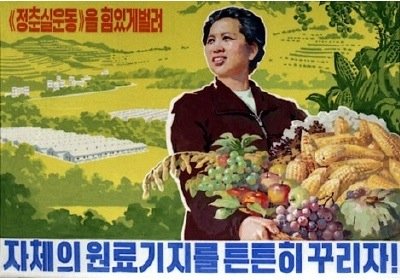

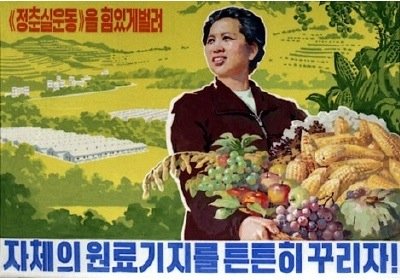

Still, it wasn’t quite what I expected; I thought it would mainly be about the political aspects of living in a communist personality cult: the parades, the synchronised gymnastics, the patriotic hymns, the giant floodlit statue of the Dear Leader, the propaganda. All of which does feature, particularly at the start of the book, but because of the period it covers (Kang was born in 1986), it is overwhelmingly about the famine. Even a mad personality cult struggles to maintain its energy in the face of millions of deaths. Not that there is much sign of the state losing its iron grip on the population, but everyday life becomes completely dominated by the famine, which is apocalyptic in scale. It is like reading Solzhenitsyn’s descriptions of scrabbling for nourishment in the gulag, except it’s not a gulag, it’s a whole town, a whole community — except of course for the party officials.

The official slogans changed as the famine ravaged the country. At the very beginning, in 1995, the cadres encouraged us o accept what was called a ‘forced march towards victory’. The term referred to the ‘forced march’ undertaken by Kim Il-Sung and his partisans during the war against the Japanese occupying forces. The following year, the battle-cry was ‘Let us speed up the forced march towards the final victory.’ When the hunger had reaches its worst, another new slogan appeared: ‘Let us not live today for today, but let us live today for tomorrow’. By now, the poorest people had been reduced to eating boiled pepper leaves or bean leaves. Some families came to us to beg us for left-over tofu that my mother cooked, or even the whitish liquid produced when it was being made. They drank it mixed with saccharine. After a certain period of time their faces swelled up. When I saw people with puffy faces tottering towards the house, I knew that was what they were coming for. Shortly after that we too had to start eating pine bark.

The end of the books is about the family’s escape, firstly into China and then through Vietnam and Laos to Cambodia, from which they went to South Korea.

It is a remarkable story. It’s not especially well written, though. It would be unfair to call the prose ‘bad’, but it is a very plain, methodical recital of events. It has very little in the way of descriptive detail and very little emotional content or insight. Definitely worth reading for the content, though, if not for the prose.