The final chapter of The Origin of Species — Darwin’s ‘Recapitulation and Conclusion’ — states the case for evolution as well as any short account I have ever read. It’s tightly written, it argues a case, it summarises all the different kinds of evidence and shows clearly why they are important. It’s pithy, confident: great stuff.

Which left me feeling look, Darwin, if you can write like that, why have the previous 400 pages been such hard work? Because he did produce some turgid paragraphs. He’s better when he’s talking about specifics — particular animals and experiments — but when he gets into generalities and abstract ideas, his prose often turns to mush. Here’s a sample sentence:

The forms which possess in some considerable degree the character of species, but which are so closely similar to other forms, or are so closely linked to them by intermediate gradations, that naturalists do not like to rank them as distinct species, are in several respects the most important for us.

OK, that’s not particularly difficult to understand, but it doesn’t have a lot of oomph, either. Not much forward momentum to keep the reader going.

That sentence is taken from the chapter ‘Variation under nature’, and part of the problem in that chapter and elsewhere is that Darwin is struggling against the limitations of his knowledge. Variation and heredity are absolutely central to the idea of natural selection, so of course he has to talk about them a lot; but without knowing about genetics, let alone DNA. And at times he seems to be floundering a bit. I’m very aware, reading it, of how much he doesn’t know; I’m curious how much he felt that lack of knowledge himself. He certainly had enough evidence of other kinds to argue convincingly that all living things evolved from a common ancestor, and that natural selection was a plausible explanation for how it happened; but without genetics there is certainly a jigsaw piece missing.

That’s not the only gap which is obvious with hindsight: for example, he talks about the distribution of species as evidence for common descent, but without continental drift, there are certain details he can’t quite explain. So if someone wanted to understand evolution, they should start with a more modern text. I suppose the question is: why read The Origin at all? Well, the immediate reason I re-read it is that we’re currently building up to Darwin Year. 2008 is the 150th anniversary of the first publication of the Darwin/Wallace theory of natural selection at a meeting of the Linnean Society, and 2009 is both 150 years since the publication of The Origin of Species and also Darwin’s 200th birthday.

Also, it may be hard going by the standards of modern popular science writers, but for one of the key documents in the history of science, it’s incredibly (perhaps uniquely) accessible. I haven’t actually tried reading James Clerk Maxwell’s original papers on electromagnetism, or Einstein’s on relativity, but I don’t think it’s defeatist to say I wouldn’t understand them. Darwin is entirely manageable for a non-technical reader. He uses some technical terminology without defining it, so you might be checking the glossary a bit if you don’t know, for example, that ‘cirripedes’ are barnacles; but the book is mostly dealing with familiar concepts and entities: species and varieties, pigeons, bees, flowers. The only comparison that springs to mind is another book written at the early stages of a science, when scientists were still grappling with everyday concepts and the visible world: Galileo’s Dialogue Relating to Two New Sciences (which, by the way, is well worth reading).

And when Darwin hits his stride, when he gets stuck into the details, the book is still full of interesting material. For example, discussing the means by which plants are distributed between places:

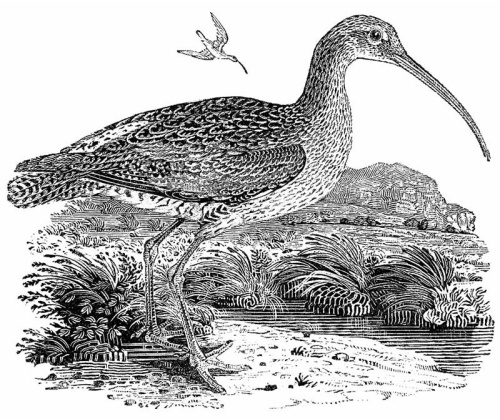

I do not believe that botanists are aware how charged the mud of ponds is with seeds. I have tried several little experiments, but will here give only the most striking case. I took, in February, three table-spoonfuls of mud from three different points, beneath water, on the edge of a little pond. This mud, when dry, weighed only 6¾ ounces. I kept it covered up in my study for six months, pulling up and counting each plant as it grew. The plants were of many kinds, and were altogether 537 in number; and yet the viscid mud was all contained in a breakfast cup! Considering these facts, I think it would be an inexplicable circumstance if water-birds did not transport the seeds of fresh-water plants to vast distances, and if consequently the range of these plants was not very great. The same agency may have come into play with the eggs of some of the smaller fresh-water animals.

That passage is a great demonstration of Darwin’s practical turn of mind. For someone who is known for having produced a famous theory, he was a great experimentalist. Faced with the argument that, for example, seeds couldn’t be distributed on ocean currents because salt water would kill them, he tried the experiment, leaving seeds in salt water for different periods of time to see if they would still germinate. He wanted to know more about the process of selective breeding in domestic animals, so he started breeding fancy pigeons. He wanted to know how inherited instinct could enable bees to make such elaborate and perfect honeycombs, so he provided a hive of bees with specially prepared blocks of wax to see what they would do with them.

If anything the book is more convincing as an argument for the historical fact of evolution — common descent with gradual changes over time — than the theory of natural selection. He does make a good case for natural selection, mainly by analogy with selective breeding in domestic animals, but because he didn’t know about genetics or DNA, there’s an inherent fuzziness about the details right at the centre.

But his argument for evolution is I think particularly strong because he was consciously writing for an audience of educated people who believed in the immutability of species. So he points out that varieties (what we now usually call subspecies) blur indistinguishably into species, so that experts frequently disagree whether to classify them as full species or not. That different continents have basically different flora and fauna; so the animals in the Amazon are related to those of the Andes rather than those of the Congo, even though the Congo is a much more similar habitat. And oceanic islands normally have very limited fauna; that what they do have tends to be those animals that can fly (insects, birds and bats, but not other mammals) or can survive salt water (reptiles but not amphibians). And again, that the inhabitants of those islands are related to the inhabitants of the nearest continent, even when the island habitat is quite different. All these facts are easily explained by evolution; there is no reason why any of them would need to be true if species were created in place.