So, I saw five films this year. Some quick notes:

Story of my Death [Història de la meva mort].

The LFF said:

Albert Serra’s teasing period-piece sees Casanova and Dracula meeting as Enlightenment reason gives way to the dangerous passions of the Romantic era.

Which sounded like it might be fun, if perhaps a bit silly. Maybe a trifle camp. In fact it was surprisingly boring.

I like the fact that artier films can allow themselves to be a bit slow-paced, and a use longer takes and longer shots: if nothing else it makes a change from the freneticness of commercial cinema. But allowing yourself to be leisurely, and give the characters room to breathe, doesn’t mean that every scene has to be like that, that every shot has to carry on for several seconds longer than necessary. And if you are going to make a film like that, and it ends up being nearly two and a half hours long, it starts to feel a little bit self-indulgent.

The director said in the Q&A afterwards that he’d never seen any genre films because he wasn’t interested in them, which explained why his handling of the Dracula scenes was so artless; artless mainly in a bad way.

On the positive side: it often looked good, and among the completely amateur Catalan cast, Casanova in particular was excellent.

The LFF said:

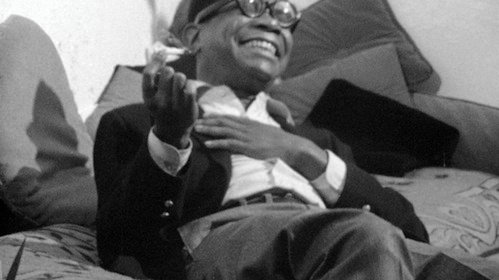

Shirley Clarke’s cinéma-vérité masterpiece about a gay African-American cabaret performer and prostitute revealingly restored.

This is a black and white documentary from 1967; Jason Holliday is interviewed in his apartment about his life as a house boy, prostitute, hustler and would-be cabaret performer as he gets steadily drunk and stoned. He is the only person we see; he replies to questions from off-camera and spins yarns which may or may not be strictly true. It’s very rough-looking; the restorer spent years looking for a good quality print before finding that what was marked as out-takes in the archive was in fact the edited film, which is complete with conversations between the director and the cameraman, moments when the screen goes black, shots out of focus and so on. But apparently there are pages and pages of editing notes to prove that this is a very carefully crafted version of roughness.

I enjoyed it, Jason is a fascinating, charming and rather tragic figure, and the style is interesting too.

Paul-Julien Robert’s quietly devastating documentary revisits the former residents of the experimental 1970s free-love commune in which he grew up.

Paul-Julien Robert didn’t know who his biological father was until he was 12, in 1991, when the Friedrichshof commune was dissolved and as part of the fall-out the various children were given blood tests to determine paternity. In this documentary, he talks to his mother, to the various men who were potential fathers, and to the other children who lived there with him. It is fascinating stuff, especially because the leader of the commune, Otto Muehl, was obsessed with documenting the life there, so the interviews are intercut with lots and lots of footage of the commune in action.

It starts out seeming fun and quirky; slightly bonkers, but free-spirited, well-meaning and optimistic as well. But it gets steadily darker, as it gradually becomes clear that a free-love commune built on the eradication of the nuclear family is not in fact a great environment for raising children. Not, at least, if it is being run by a controlling egomaniac.

It’s fascinating on all sorts of levels, not least the disconnect between the adults’ experience of the commune and the children’s. Apparently it was only really when making the film that he felt able to talk openly about his childhood, and there are some particularly painful conversations with his mother.

A Chadian street photographer’s romantic interest in a would-be model lands him in a murky criminal underworld in this smart thriller.

To be pedantic about it, he’s not actually a ‘street photographer’ as I would understand it; he’s not taking candid shots of urban life. He takes photos for ID cards and the like. He’s also a nightclub dancer with a withered leg.

The thriller-y bits could have been edited a bit more snappily, perhaps, but basically I enjoyed this. It usually looks good, it has plenty of plot, which is sometimes a bit lacking at the kind of films I tend to go to at the festival, and the central performances are good. And a pretty girl and some good dance sequences.

The Eternal Return of Antonis Paraskevas [Η Αιώνια Επιστροφή Του Αντώνη Παρασκευά]

A dark satire on current Greek woes that sees a failing TV personality stage his own kidnapping, only to start to unravel as he holds himself hostage.

This is an almost silent film. Paraskevas is holed up in an empty hotel alone while the world thinks he has been kidnapped, and for most of the film the only dialogue is from the TV news and videos he is watching. He is already perhaps a little unstable to have thought this was a good idea, but the solitude pushes him further over the edge and the initially comic tone turns darker.

It’s genuinely funny in the funny bits, and the turn to the dark works as well. There are perhaps a couple of mis-steps along the way, but generally I really liked it. Christos Stergioglou is great in the central role; there’s an almost Buster Keaton quality to the way he manages to be silently expressive with a mournful and impassive face.