This is the Werner Herzog documentary about the Chauvet cave paintings in France. It was definitely worth seeing, but mainly, I think, for the incredible paintings themselves, rather than anything Werner Herzog brought to the project.

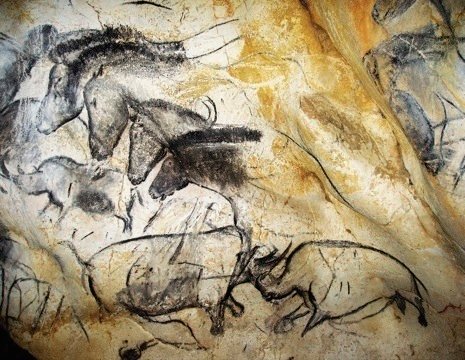

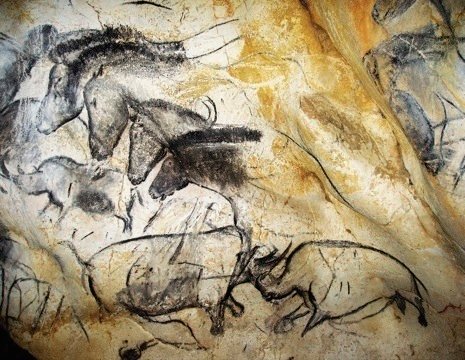

It is probably the best use of 3D I’ve seen, because although I’ve seen photos of the paintings at Chauvet and Lascaux, the photos tend to flatten out the image; you get very little sense of the highly irregular shape of the cave walls and the way that the paintings are shaped around the contours of the rock. The 3D film really did make all the difference and was very effective.

Which is an unusual view for me, because I basically think that 3D is a rubbish technology. In most circumstances it’s little more than a gimmick, and it seems to be technically rather bad anyway: I find that it looks unnatural and exaggerated, it’s often slightly shimmery or glitchy, it doesn’t work properly if you tilt your head to one side, and it tends to give me a headache. I don’t know if the problem is that I’m wearing prescription glasses under the 3D ones, but that seems to be a lot of downside for very little upside.

Even in this film, I think it would have been better to save the 3D for the places where it really mattered — i.e. looking at the cave paintings. An interview with a paleontologist sitting in an office does NOT need to be in 3D, thank you very much.

And even in the scenes inside the cave, it became clear that some of the film had not been filmed in 3D, but faked up as 3D in post-production. This was particularly egregious in a scene where two scientists were standing in front of a cave painting and talking about it, and something looked very weird; I suddenly realised that when they had faked the 3D, they had cut out the two figures rather carelessly and cut out a big chuck of the surrounding wall as well; so there was a big blob of cave wall which was in completely the wrong visual plane, floating in front of the wall around it.

Such technical gripes aside, the paintings were beautiful and fascinating. And there were all sorts of snippets of fascinating information, like the great scratches on the walls which had been left by cave bears sharpening their claws. Or the two stags painted on top of each other which carbon dating revealed were painted 5000 years apart. I mean, really, 5000 years! What does it mean that there was such staggering cultural continuity?

I was also interested that there was no sign of human habitation in the cave; presumably they used it as a ritual site, or something. It’s all guesswork, of course. There also no humans among the paintings, apart from one image apparently of a woman’s pubic triangle and legs, similar to the famous ‘Venus’ figurines. And no pictures of birds, incidentally; it’s all big game: cave bears, cave lions, horses, antelope, woolly rhino, mammoth, hyena, aurochs.

Of course we have so little of their lives to draw on, so what does survive gains enormous, inflated importance. The paintings are the most vivid connection we have to those people 35,000 years ago, and so we can’t help having them as central to our idea of their lives; but we don’t know whether they were similarly important to the people who painted them. The film did show a few objects found at other sites of the same period that provide a few hints at a broader life; Venus figurines, animal carvings, and most extraordinarily a flute which had been meticulously reconstructed from over 30 tiny fragments of ivory. But mainly we are left with a lot of stone tools and the cave paintings. Anything made of wood, or gut, or hide is long gone, let alone the stories they told, the music they played, the food they cooked.