-

'Europe may become a significant source of "exported" measles in poor countries that have done a better job eliminating the virus.

A study in The Lancet this week finds that the WHO is unlikely to meet its goal of eliminating measles in the European region by 2010 because vaccination rates in many countries, including Germany, the UK and Italy, are too low to stop the spread of the virus. In contrast, Latin America eliminated measles in 2002, but has since suffered outbreaks "imported" from Europe. While measles rarely kills in Europe, in poorer countries malnutrition and limited healthcare make the virus far more lethal'. That's actually the complete story, so don't follow the link. It just seemed worth flagging up. It would be nice to think that all the anti-vaccine people, the conspiracy theorists and homeopaths and fruitcakes of various persuasions, would see this news and feel deep shame, but no doubt they have their self-justifications ready.

Tag: Europe

Links

-

'These pinhole photographs, exposed for six months, capture the journey of the sun from the winter to the summer solstice.' Cool and completely beautiful.

-

interesting little article about a Victorian mummy dissection

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone by Saša Stanišić is my book from Bosnia and Herzegovina for the Read The World challenge. I actually had a different writer in mind — Ivo Andrić, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961 — but when I saw this in the bookshop I switched. Mainly because most of the books I’ve been reading are a few decades old, and it’s nice to find one which is fresh out of the oven (published in German in 2006; the English translation by Anthea Bell in 2008).

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone tells the story of Aleksandar Krsmanović, a boy who is growing up in the Bosnian town of Višegrad but flees with his family to Germany in 1992 to escape the war. Since Stanišić grew up in Višegrad and moved to Germany in 1992 as a fourteen-year-old, I assume it is somewhat autobiographical.

The blurb on the back cover compares Stanišić with Jonathan Safran Foer and David Foster Wallace, which gives you some idea of the kind of writer he is: a clever young man who isn’t afraid to leave evidence of his cleverness on the page. There are sections written in different voices, stylistic quirks, elements you might call magical realist, a bit of a book-within-a-book and so on. In fiction there can be a fine line between overtly clever and overly clever, and for the first few chapters I was a bit unsure which side of the line this book falls, but it won me over.

Here’s a fairly randomly picked passage:

My Nena went deaf the day Grandpa Rafik married the river Drina, face down. The marriage was legal because Nena and Grandpa Rafik had been divorced for years, something unusual in our town. After Grandpa Rafik was buried, they say she said at his graveside: I haven’t cooked anything, I haven’t brought anything, I haven’t put on black clothes, but I have a whole book full of things to forgive. They say she took out a stack of notes and began reading aloud from them. They say she stood there for a day and a night, and word by word, sentence by sentence, page by page she forgave him. And after that she said no more, and she never reacted to any kind of question again.

Nena Fatima has eyes as keen as a hawk’s, kyu, ket-ket, she recognises me before I turn into her street, and she wears headscarves. Nena’s hair is a secret — long and red and beautiful, she gave the secret away to me as we sat outside her house eating börek in summer and feeding the Drina with minced meat. Cold yoghurt, salted onions, the warmth of Nena rocking silently as she sits cross-legged. The dough is shiny with good fat. Nena rocks back and forth and lights a cigarette when I’ve had enough. I am the quietest grandson in the world, so as not to disturb her stillness and our sunset. Sultry heat gathers over the river and looks attentively at Nena Fatima, who is humming as she plaits her secret into a long braid. I don’t laugh with anyone as softly as with my Nena, I laugh with her until I’m exhausted, I don’t comb anyone else’s hair.

As I do the Read The World challenge, various themes are recurring; this is the third book I’ve read (along with My Father’s Notebook and The Kite Runner) which is written by a refugee, starts with nostalgic memories of the home country, and then describes the country collapsing and the refugee experience. It is much the best of the three, I think; I did genuinely enjoy The Kite Runner, but it is deeply emotionally manipulative, like watching a Hollywood film about a difficult subject by a skillful but solidly mainstream director. The kind of glossy film on a ‘brave’ subject which is daring enough to win a few Oscars but which you look back on a few years later and think… meh. How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone is a more interesting book all round; messier, more personal (I think), funnier, sadder. And while I don’t want to overstate the originality of it — it’s been nearly a hundred years since some bright spark invented modernism, FFS — it is at least less of a straight down the line conventional narrative.

» the photo is of the bridge over the Drina in Višegrad that is mentioned in How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone and is also incidentally the eponymous bridge in Ivo Andrić’s novel The Bridge on the Drina. The photo is © blandm and used under a CC by-nc-sa licence.

A European Obama

There’s an Associated Press article you can read all over the web including, for example, MSNBC, titled Europe has a long wait for its own Obama. I’m not going to comment generally on ‘Europe’, or even in detail on the UK, except to say that the most obvious difference is the relative recentness of large-scale non-white populations in Europe. It’s been 50 or 60 years now, so that excuse is wearing thin, but it’s still somewhat relevant, I think; even in a democracy, most people who reach positions of power and authority do so from a solidly prosperous establishment background, which is not the situation new immigrants are generally in. So with 8% non-white population, most of whom have been here for three generations or less, even if the UK was completely free of racial discrimination (which it obviously isn’t), the odds would probably still be against us having had a non-white Prime Minister by now. As a comparison, 6% of the population is Welsh, and we’ve only had one Welsh Prime Minister in 300 years.

And one point I’d take from the way the US election has panned out is that all votes are cast for an individual. It’s not very long ago that the press was busy asking whether America was ready to vote for a black president; the answer seems to be yes, but that wasn’t necessarily obvious in advance. You can only find out the answer by having the election; and until you have a candidate, no-one can know the answer because it’s impossible to judge your own responses until you have a real person with a name and a face and a set of policies and a campaign. America may not be ready to vote for ‘a black man’, but they are ready to vote for Barack Obama.

Similarly, it might be difficult to imagine a black or Asian prime minister, but then it would have been difficult to imagine a woman in 10 Downing Street until Margaret Thatcher came along. Do I actually think it’s going to happen any time soon? No, absolutely not. In fact, given the way the parliamentary system works, you can pretty much guarantee it won’t happen for at least six or seven years. But would the British public be willing to vote for a dark-skinned candidate for PM? It’s impossible to know, but if, like Obama, they were charismatic, eloquent, unflappable and running against a staggeringly unpopular incumbent, I wouldn’t bet against them.

A ‘Christian nation’.

There was the first of a three-part series on TV tonight called Make Me A Christian. A group of volunteers, including a lap-dancer and a Muslim convert, are given a three-week course in Christianity by four ministers of various denominations. I watched about 20 minutes of it before I lost patience; it’s an idea that could make an interesting piece of television but in practice it both bored and irritated me.

But one particular idea requires comment: that the UK is a ‘Christian nation’ built on ‘Christian principles’. I don’t think it’s true that any of the important principles that the country is built on are particularly Christian, as it happens, but that’s not the point I want to make.

It is true that, for over a thousand years, the vast majority of the inhabitants of these islands have been Christians. A comfortable majority of British people still are. So, historically and demographically, there is an obvious sense in which it is true to say that the UK is ‘a Christian country’.

But you could use exactly the same arguments to say this is a white country. And if someone was to start saying that the UK is a White nation, built on White principles, we would all immediately understand that their intention was to exclude and belittle.

I know the analogy is not perfect. And I’m not going to claim that, as an atheist, I feel like I’m the victim of any terrible prejudice (though if I was Hindu, Muslim or Jewish I might feel differently). But when an evangelical preacher like the presenter of Make Me A Christian describes the UK as a ‘Christian country’, I’m pretty sure he’s suggesting that his claim to Britishness is better than mine.

I do not accept that this is true.

» The picture is of a Christian being burnt by Christians because of his Christian beliefs; an example of the Christian principles so important to British history.

Lies, damn lies and religion

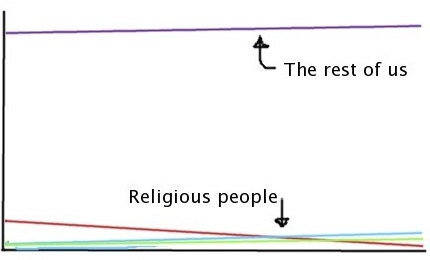

There’s an article in today’s Times about the rapid decline in church attendance in the UK. The particular angle they’ve chosen to take is that within a mere 30 years, the number of people going to mosque every weekend will outnumber those going to church. This is illustrated by a dramatic graph with the Christian line sweeping down at a vertiginous angle and crossing the lines for Muslims and Hindus, which are creeping up a bit slower at the bottom.*

Leaving aside the huge uncertainties involved in extrapolating the trends forward, I can’t help feeling that the graph is missing something important: a line for the vast majority of us who don’t go to any kind of religious service. If they had included us, and changed the scale of the y-axis to accommodate us, all the religious people would be squashed down into a very flat and unimpressive bit at the bottom of the chart.

Of course it’s an interesting and significant demographic shift if the number of churchgoers changes from about 8% to 1% in 45 years, as the graph suggests. But if you say instead that the number of people who don’t go to church/mosque/temple regularly is rising from 90% to 94%, it doesn’t seem quite so dramatic.

As regular readers will know, I’m not about to lose sleep over shrinking congregations; and I certainly don’t believe there’s some kind of essential connection between Britishness and Christianity. But I was mainly annoyed by the use of statistics.

*The graph isn’t available online or I’d link to it. The Times’s consistent habit of having less in the way of pictures and graphics online than in the dead tree edition always seems to be completely missing the point, to me, but hey-ho.